U.S. Death-Row Population Lowest in More Than 32 Years But More Racially Disproportionate

A Death Penalty Policy Project Analysis

The number of people on death row or facing possible capital resentencing across the United States is lower than at any time in the past 32 years but has become increasingly racially disproportionate, according to data compiled by the Legal Defense Fund (LDF) and analyzed by the newly established Death Penalty Policy Project (“DP3”).

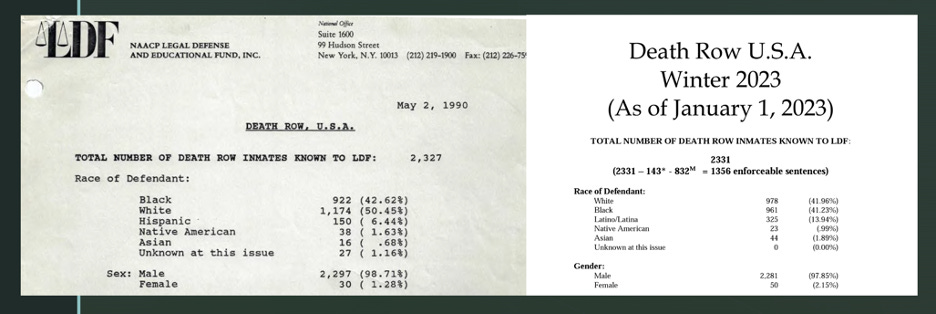

LDF has just released its most recent quarterly death-row census, the Winter 2023 edition of Death Row USA (DRUSA). LDF reports that 2,331 men and women were imprisoned on state, federal, or military death rows in the United States or faced continuing jeopardy of death in pending capital retrial or resentencing proceedings as of January 1, 2023. That was the fewest number of people sentenced to death in the United States since May 1990, when LDF reported that 2,327 prisoners were on the nation’s death rows or facing capital resentencings. Since that time, the percentage of death-row prisoners who are persons of color has risen by 18.6%, an increase in nine percentage points from 49.0% to 58.0%.

DP3 compared that census to past LDF data and other historic death-row data sets to assess the extent of the increasing racial concentration of BIPOC individuals on U.S. death rows and to identify mechanisms that are contributing to that increasing concentration. Our review was not exhaustive and more research needs to be done, but what we found supports the proposition that race disparities are endemic in the administration of the U.S. death penalty.

As the use of death penalty expanded in the U.S., individuals of color faced a comparatively increased risk of being sentenced to death. That comparative risk increased further as death-penalty usage declined, particularly for defendants who were young or intellectually disabled, defendants in large urban or suburban counties, and in cases of likely innocence. As death row continued to shrink, a White-defendant preference in grants of mercy and White-victim preference in executions further increased the disproportionate concentration of BIPOC individuals remaining on death row or facing capital retrial and resentencing proceedings.

The Increasing Racial Concentration of U.S. Death Rows

The U.S. death-row population reached its peak in July 2001 when 3,717 men and women faced active death sentences or continuing jeopardy that a death sentence that had been overturned would be reimposed on appeal or in pending retrial or resentencing proceedings. The Winter 2023 DRUSA reveals that the number of people sentenced to death or facing reimposition of the death penalty has declined since then by 1,386 — a drop of 37.2%.

When the U.S. death-row population peaked in the summer of 2001, 2,021 of the men and women facing jeopardy of execution were people of color (54.4%). A decade later, the number of people on death row or facing capital retrial or resentencing proceedings in the U.S. had fallen to 3,220, down 13.4%. Although the number of death row prisoners of all races declined, the White death row population fell by 297 (17.5%) while the population of death row prisoners of color fell by 200 (9.9%) to 1,821. As a result, the proportion of death row comprised of individuals of color rose to 56.6%.

That pattern persisted over the next decade as the U.S. death-row population continued its decline. The Summer 2016 DRUSA reported that 2,905 people were on death row or facing jeopardy of capital resentencing, a five-year drop of 9.8%. During that time, the number of White death-row prisoners fell by 168 (12.0%) to 1,230, while the number of death row prisoners of color declined by 147 (8.1%) to 1,674. The proportion of death row comprised of individuals of color again increased, rising to 57.7%.

From 2016 until January 2023, death row fell by another 574 people to 2,331, a 19.8% decline. Again, proportionally more White prisoners (252, 20.5%) came off death row than did prisoners of color (321, 19.2%). The percentage of those on death row or facing jeopardy of capital resentencing who were individuals of color rose again to 58.0%, although the rate at which the racial disproportionality increased slowed significantly.

The increasing racial disproportionality of U.S. death row is even more notable when considered against the backdrop of developments in two of the most prolific death sentencing counties in the U.S. in the 20th century: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Cook County (Chicago), Illinois. In 2001, those counties had the third and fourth largest death rows of any counties in the country and accounted for more than ten percent (10.9%) of all the BIPOC individuals on death row or facing possible capital resentencings in the U.S. But (for very different reasons) by 2023 they were no longer using the death penalty.

My July 2001 study of the Racial composition of death row in the seventy most populous counties in states with the death penalty found that Philadelphia had 121 people of color among its then 134-person death row (90.3%), including more African Americans (112) than any other county in the country. Among counties with 30 or more people on death row, it had the highest percentage of Black death-row prisoners (83.6%), the highest percentage of death-row prisoners of color, and the highest per capita death-row population of people of color (13.9 per 100K population). The July 2001 Death Row USA reported that, at that time, 69.7% of Pennsylvania’s 244-person death row were individuals of color, 154 of whom were Black (63.1%), 14 Latinx (5.7%), and 2 Asian (0.8%).

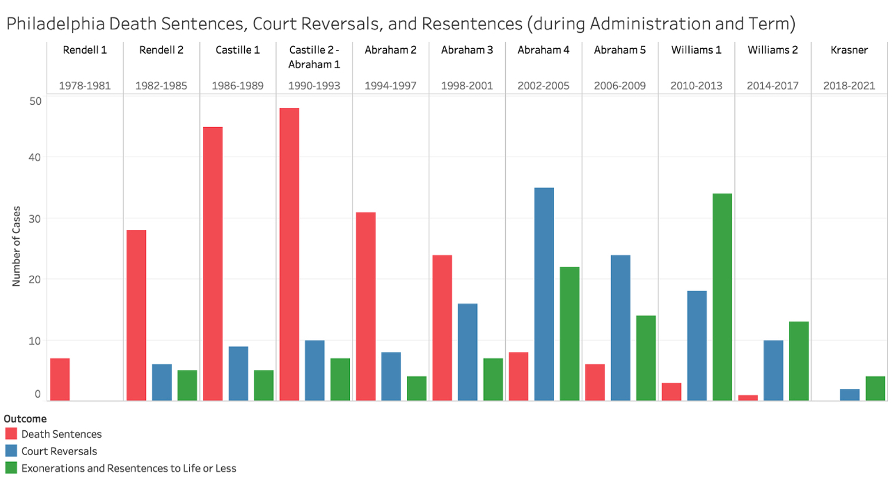

Figure 1. Death sentences have declined dramatically in Philadelphia since the 1990s, essentially disappearing by the time Larry Krasner took office in 2018. (Death Penalty Information Center Graphic by Patrick Geiger for Robert Brett Dunham, The Death Penalty in Philadelphia, Nov. 2018).

But after peaking in 2001, Philadelphia’s death penalty collapsed, as death sentences declined (Figure 1) and death penalty reversals and non-capital resentencings soared (Figure 2). In Lynne Abraham’s fourth and fifth terms as Philadelphia District Attorney, new death sentences fell to fewer than two per year while more than fifty death sentences were overturned in the courts without a single death sentence reimposed. By the time voters elected reformer Larry Krasner as district attorney in November 2017, Philadelphia juries were no longer returning death sentences and capital sentencing had already come to a virtual halt. In January 2021, without a single execution, only 38 people remained on Philadelphia’s death row or faced potential capital resentencing — an astonishing decline of 71.6%. As of March 23, 2023 — the Pennsylvania Department of Correction’s latest death-row update — Philadelphia’s death row was down to 21, 84.3% below its peak.

Figure 2. The decline in new death sentences imposed in Philadelphia was accompanied by dramatic increases in the number of death sentences reversed in the courts and resolved with non-capital outcomes. (Death Penalty Information Center graphic by Patrick Geiger for Robert Brett Dunham, The Death Penalty in Philadelphia, Nov. 2018)

As Philadelphia death sentences declined, however, their racial disproportionality intensified. Forty-four of the final 46 death sentences imposed in Philadelphia before Krasner took office were directed at defendants of color — 95.7% of the new death sentences (Figure 3). The bulk of those sentences were imposed on Black defendants (38, or 82.6%), though five others were imposed on Latinx defendants (10.9%), and one more on an Asian defendant (2.2%). Two death sentences were imposed on White defendants (4.3%).

Figure 3. (Death Penalty Information Center graphic by Dane Lindberg for Robert Brett Dunham, The Death Penalty in Philadelphia, Nov. 2018)

Exonerations, death-row deaths, and non-capital resolution of overturned death sentences reduced Philadelphia’s death row to 38 individuals by January 1, 2021. Yet these reductions left the racial disproportionality of the county’s death row — already huge in 2001 — even more pronounced: 35 of those still facing jeopardy of death were people of color (92.1%), including 32 Black (84.2%), 2 non-Black Latinx (5.3%), and 1 Asian (2.6%). Since then, two of the three White death-row prisoners have come off the row (66.7% of the January 2021 total), along with 15 BIPOC individuals (42.9%). The remaining 21 death-row prisoners are now 95.2% individuals of color: 18 Black (85.7%), and one each White, Latinx, and Asian (each 4.8%).

Paradoxically, the increased racial disproportionality of Philadelphia’s death-row population decreased the racial disproportionality of Pennsylvania’s death-row population. Why? Because the proportion of people of color who came off of the county’s death row was greater than the proportion of individuals of color on death row across the state.

In 2001, nearly fifty-five percent of those on death row or facing jeopardy of capital resentencing in Pennsylvania had been sentenced to death in Philadelphia, but the county accounted for 70.8% of the state’s death-row prisoners of color (121 of 171). By the time of the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections’ March 2023 death-row listing, defendants from Philadelphia comprised only 20.8% of the state’s far smaller death row (101 people), and just over one third of the state’s death-row prisoners of color (20 of 56, 35.7%).

So, despite the overwhelming and increasing racial disproportionality of Philadelphia’s death row, the diminished size of the county’s death row reduced the percentage of people of color on the Commonwealth’s death row to 55.4%.

Like Philadelphia, Cook County had an overwhelmingly racially disproportionate death row. Seventy-four of its 86 death sentenced defendants on death row or facing capital resentencings in July 2001 (86.0%) were individuals of color, including 70 Black defendants (81.4%) and 4 Latinx (4.7%). Cook County accounted for 57.9% of Illinois’ death-row prisoners of color and nearly two-thirds (63.1%) of its Black death-row prisoners. Statewide, 175 capitally sentenced prisoners were on Illinois’ death row or faced jeopardy of death in pending resentencing proceedings. 121 of these men and women (69.1%) were Black (111, 63.4%) or Latinx (10, 5.7%). All of these people came off death row as a result of court rulings, grants of clemency, or the Illinois legislature’s abolition of the state’s death penalty.

In Philadelphia and Cook counties alone, the past two decades have produced a net reduction of 175 BIPOC death-row prisoners and 25 White death-row prisoners, or 11.2% of the nationwide 668 net reduction of death sentenced individuals of color and 3.5% of the nationwide 717 net reduction of White death-row prisoners. Excluding Philadelphia and Cook counties from the count reveals the even more disturbing increase in the racial disproportionality of death row in the rest of the country. There, the concentration of BIPOC individuals on death row has risen 13.5%, an increase of 7.1 percentage points from 52.2% BIPOC (1,826 of 3,496) in July 2001 to 59.3% (941 of 2,310) in 2023.

The Racially Disproportionate Imposition of the Death Penalty on Vulnerable Populations

More research is needed the identify the range of factors that have contributed to the increasing racial disproportionality of the U.S. death penalty. However, one contributing cause already is clear: the death penalty is grossly racially disproportionate as applied against the most vulnerable classes of defendants.

My review of data concerning the use of capital punishment against individuals with intellectual disability found that as of February 1, 2023, 118 of the 142 death-row prisoners whose death sentences had been vacated as a result of intellectual disability are persons of color — 83.1%. More than two-thirds are African American (97, or 68.3%); 16.9% (24) are White; 14.1% (20) are Latinx; and one (0.7%) is Asian. Eleven (7.7%) are foreign nationals, representing nearly 5% of all foreign nationals known to have been sentenced to death in the U.S. More than three-quarters of the 29 likely intellectually disabled death-row prisoners who have been executed since Atkins declared that practice unconstitutional have been individuals of color (22, 75.9%). Close to two-thirds (18, 62.1%) were Black; 24.1% (7) were White; and 13.8% (4) were Latinx.

The data on the use of the death penalty against juvenile and late adolescent offenders highlights the heightened vulnerability of Black defendants to extreme punishments and the increasingly disproportionate application of capital punishment against individuals of color in the U.S.

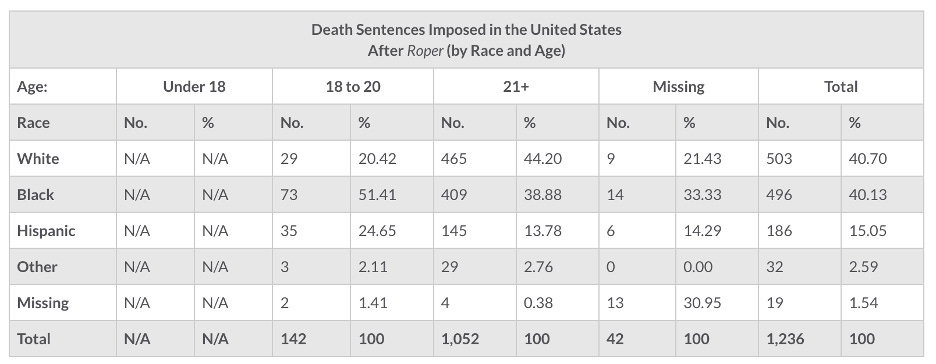

University of North Carolina political scientist Frank R. Baumgartner assembled a database of more than 8,700 death sentences imposed in the United States between the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1972 decision in Furman and the end of 2021. Broken down by the age and race of the defendant, Baumgartner was able to provide a racial breakdown of the number of defendants under age 18, ages 18 to 20, and age 21 or older at the time of the offense who have been sentenced to death, including a subset of data reporting on all death sentences imposed after Roper v. Simmons struck down capital punishment for crimes committed by offenders younger than age 18. Using that data, I calculated the race and age characteristics of the defendants sentenced to death prior to Roper and compared them to the post-Roper numbers.

Figure 4. Tables from my DPIC analysis: Report: Racial Disparities in Death Sentences Imposed on Late Adolescent Offenders Have Grown Since Supreme Court Ruling Banning Juvenile Death Penalty, August 29, 2022.

The analysis revealed a disturbing pattern: the younger the age class, the more disproportionally likely it was that the death-sentenced defendant would be a person of color. Moreover, juvenile and late adolescent Black defendants faced an elevated risk of being sentenced to death in the pre-Roper time frame when both groups were eligible for capital punishment. This most likely reflected the combined effect of “adultification” — the phenomenon by which Americans disproportionately ascribe adult characteristics to young Black individuals — and the pernicious racial stereotype that young Black males are dangerous.

Prior to Roper, 61.3% of death sentenced juveniles and 59.3% of death-sentenced late adolescent offenders were defendants of color. African Americans comprised 48.9% and 48.5% of juvenile and late adolescent offenders who were sentenced to death, ten percentage points higher than the percentage of death sentenced African Americans aged 21 or older. Latinx defendants comprised 11.1% of juvenile offenders sentenced to death, 8.8% of late adolescents, and 5.9% of death sentenced offenders aged 21 or older. By contrast, White defendants comprised 32.7% of juveniles, 35.1% of late adolescents, and 48.8% of offenders aged 21 or older sentenced to death.

After Roper, the percentage of death-sentenced late adolescents of color rose by 18.9% percentage points to 78.2%, while the percentage of death-sentenced late adolescents who were White dropped by 14.7 percentage points to 20.4%.

The sentencing data also shows that, at the same time the number of death sentences has declined in the U.S., racial disparities in sentencing have increased. Death sentences peaked in the United States in the mid-1990s, with more than 300 new death sentences imposed per year. They have declined by approximately 90% since then, including a 70% drop in the decade before the pandemic. Fewer than 50 new death sentences have been imposed in the U.S. every year since 2015.

Death-row exonerations also point to the heightened vulnerability of BIPOC defendants in death penalty cases. As I explained in the Death Penalty Information Center’s February 2021 Special Report: The Innocence Epidemic, “Wrongful capital convictions are not race neutral. DPIC’s exoneration data shows that exonerees of color, and particularly those who are Black, are more likely to be victims of official misconduct and false accusation, more likely to be wrongfully convicted and condemned, and more likely to spend longer periods facing execution or under the continuing shadow of their wrongful conviction than white death-row exonerees.”

The Death Penalty Census database of more than 9,700 death sentences imposed since states began adopting new capital sentencing procedures in response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Furman v. Georgia in 1972 found that defendants of color color constitute slightly more than half of those sentenced to death over the past 50 years (52.8%). At the same time, they now make up 64.6% of the nation’s 192 death-row exonerations.

But Baumgartner’s data shows that whatever the cause of the racial disproportionality of U.S. death rows, the problem has gotten worse over time. From 1972 to March 2005, 48.0% of all people sentenced to death were defendants of color and 45.5% were White. (Race data was unavailable for 6.9%.) White death-sentenced defendants outnumbered African Americans by 6.4 percentage points. Since Roper, the data indicate that 57.8% of all defendants sentenced to death have been people of color, while 40.7% have been White. (Race data was unavailable for 1.5%.) The number of White and Black death-sentenced defendants has been nearly equal, with White death-sentenced defendants outnumbering African Americans by less than six tenths of a percentage point.

For analyzing sentencing trends in the U.S., there is nothing magical about the year in which Roper was decided. We have the data for the years before and the years after, and Roper becomes a proxy for time. One think we know, however, is that the decline in U.S. death sentencing began nearly a decade before Roper. And that tells us that the racial disparities associated with the decline in U.S. death-penalty usage are likely even greater.

The Racially Disproportionate Impact of Large Outlier Counties

Large urban and suburban counties that have bucked the trend of declining death rows — or at least have delayed the trend’s onset — also reflect the increasing racial concentration of death row. I am currently working on an update of my 2001 study, comparing the January 2021 death rows of the 70 largest counties in the U.S. that had the death penalty in 2001 to their death rows in July 2001. The final numbers have not yet been verified, but a preview of that study indicates that the urban outliers are also becoming more racially disproportionate.

In 2001, I found that these 70 counties accounted for 1,661 of the 3,717 men and women the Summer 2001 DRUSA said were then on death row or facing continuing jeopardy of death in retrial or resentencing proceedings. That amounted to 44.9% of death row. 1,048 of those then in the death penalty’s crosshairs were individuals of color, or 63.09% of death row.

As a result of legislative or judicial action, 24 of those counties are in states that no longer have a death penalty. Furthermore, local voters have drastically changed the status of capital punishment in the three counties that had the largest death-row populations in 2001 — Los Angeles (CA), Harris (Houston, TX), and Philadelphia (PA). And, as mentioned earlier, capital punishment had been legislatively abolished in Illinois, home of Cook County, formerly the nation’s fourth largest county death-row.

Collectively, the death-row population of the 70 largest counties had declined by 23.2%, to 1,275 by January 2021. People of color accounted for 852 of those in jeopardy of execution, down 18.7%. So, while 386 fewer individuals were facing the death penalty or possible capital resentencing in those counties, barely half of that decline (196, 50.8%) was among prisoners of color. Altogether, the percentage of death-row prisoners of color in these counties rose to 66.8%. That 3.7 percentage-point increase meant that death row in these counties was nearly six percent more racially concentrated than it had been two decades before (5.9%).

Moreover, all of the eight outlier counties among the 70 that experienced increases in their death-row populations exhibited greater racial disproportionality. Riverside County, California, had the largest net increase of any county in the country in the size of its death row, more than doubling from 45 to 92. That is a 104.4% increase in a state that most likely will not execute any of its death-row prisoners. With a net increase of 47 death-row prisoners, Riverside surged from the nation’s seventh largest county death row to second in the country. And with a net increase of 20 Latinx, 15 Black, and one Asian death-row prisoners, Riverside’s already racially disproportionate death row (73.3% individuals of color) reached 75.0% BIPOC.

Los Angeles County remained the nation’s largest county death row. Prior to the election of reform prosecutor George Gascón as district attorney, Los Angeles’ death row had increased by 45 men and women, from 177 to 222. That 25.4% net increase in size was entirely at the expense of defendants of color. Between 2001 and 2021, the net number of White death-row prisoners decreased by more than a quarter (25.6%), from 39 to 29, while the net number of individuals of color on death row or facing capital retrials or resentencings rose by nearly forty percent (39.9%), from 138 to 193. The 109 African Americans on the county’s death row as of January 2021 was 25.3% larger than in July 2001 (87). While that was still fewer than the 112 African Americans who had active death sentences or faced capital reprosecution in Philadelphia in 2001, Los Angeles’ Black death row in January 2021 was larger than any other county’s entire death row.

The Latinx population of Los Angeles’ death row increased even more disproportionately, rising by more than three-quarters (77.5%), from 40 to 71. Including Asian, Native American, and other people of color sentenced to death in Los Angeles, the county’s BIPOC death-row population has grown by 55, from 138 to 193, and is now more than double the size of any other county’s entire death row. In 2001, 78.0% of those on death row or facing capital reprosecution in Los Angeles were individuals of color. By 2021, that figure had increased to 86.9%, second only to Philadelphia (92.1%) among the counties with more than 10 people still on death row.

Each of the other counties that had double-digit net increases in the size of their death rows also exhibited significant increases in racial disproportionality. Death row in Maricopa County (Phoenix) increased in size by more than half (52.7%), from 55 to 84. The county saw a net increase of 8 White death-row prisoners (21.6%), while the number of BIPOC individuals facing active death sentences or capital reprosecutions more than doubled (116.7%), from 18 to 39. That rate of increase was 5.4 times greater than the increase for White defendants. The proportion of Maricopa’s death row comprised of individuals of color increased by more than forty percent (41.9%) between 2001 and 2021, from less than one-third BIPOC (32.7%) to more than 4 in 9 (46.4%).

Orange County, California’s death row grew from 45 to 62, a net increase of 37.8%. The entire net increase of 17 death row prisoners consisted of defendants of color. The BIPOC percentage of Orange County’s death row leapt by 15.2 percentage points, from 44.4% to 59.7%, amounting to a 34.3% increase in the ratio of BIPOC death-row prisoners to White death-row prisoners.

Duval County, Florida was the other county that had a double-digit increase in its death-row population, up by 16 between 2001 and 2021. Its 42.1% increase in size featured a net increase of two White and 15 Black death-row prisoners, and a net decline of one Latinx death-row prisoner. The Black population of death row increased by 78.9%, at a rate 7.1 times greater than the 11.1% increase in the White death-row population. The percentage of BIPOC individuals on death row or facing capital reprosecution in Duval County rose more than ten percentage points, from 52.63% to 62.96%.

White-Victim Preference and the Effect of Executions on the Increasing Racial Disproportionality of U.S. Death Row

Executions have also contributed to the increasing racial disproportionality of U.S. death row.

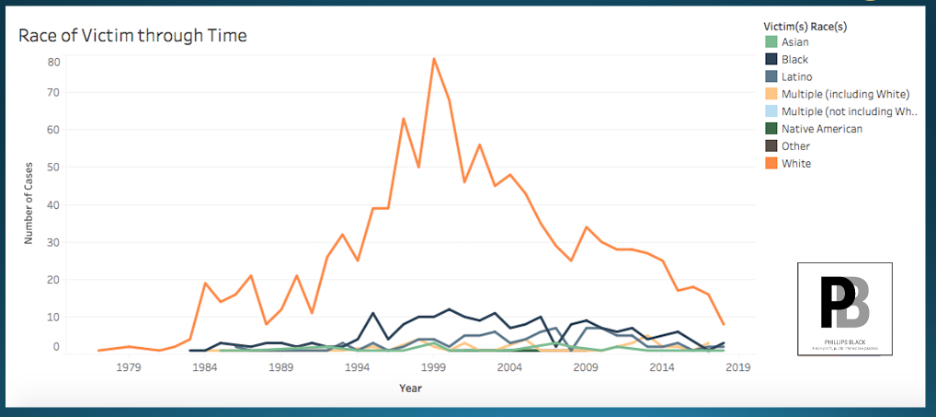

The data have long shown race-of-victim effects that simultaneously mask and demonstrate racial bias against defendants of color in the application of the U.S. death penalty. The execution statistics by race of defendant and race of victim reported in the Winter 2023 DRUSA (Figure 4) document both the overwhelming White-victim bias in death penalty usage (75.4% of victims) and race-of-defendant disproportionality.

Figure 5. Deborah Fins, Death Row USA Fall 2023, Execution Update, Legal Defense Fund (August 2023).

LDF’s race-of-defendant/race-of-victim data show that 92.5% of White defendants who are executed are put to death on charges of killing White victims (805 of 870). It is 12.4 times more likely that a White death-row prisoner who is put to death will have been executed for a same-race murder than for an interracial murder.

By contrast, nearly two-thirds of executions of Black prisoners are for interracial murders (65.7%), and in 56.3% of the cases in which Black prisoners are executed, the victim or victims all are White. It is 1.6 times more likely than an execution of a Black defendant involves a White victim than a Black victim.

That executions disproportionally involve White victims highlights the inappropriate race-based conception of what constitutes the “worst of the worst” killings in the U.S. death penalty system. This results in both an overpunishment of White defendants who commit the vast majority of White-victim murders and a proportionately greater overpunishment of Black defendants in White-victim cases.

Figure 6. Executions Over Time by Race of Victim.

This has created a second apparent paradox: the White-victim preference in executions in the U.S. has increased the racial disproportionality of the remaining death-row population. U.S. states and the federal government executed 836 people between July 1, 2001 and January 1, 2023, from the peak size of U.S. death row to the date of the latest LDF Death Row USA. Of those executed, 468 were White (56.0%) and 368 were death-row prisoners of color (44.0%). Nearly three quarters of the executions during this time involved cases with one or more White victims (74.6%), slightly below the historical average. An even greater percentage of the White prisoners who were executed (437, or 93.4%) and more than half of the executed prisoners of color (187, or 50.8%) had been sentenced to death in cases involving at least one White victim.

The Bottom Line

Everywhere in the world in which the death penalty exists, it is applied disproportionately in cases involving favored classes of victims and disproportionately against disfavored classes of defendants. As a corollary, when mercy is granted, it is disproportionately dispensed towards more favored classes of defendants.

The U.S. experience is no different. And that endemic defect in capital punishment may go a long way towards explaining why, even as the death penalty declines across the United States, death row has become increasingly racially disproportionate.

Note: Graphics credits updated on September 1, 2023. Data is from cited sources. Data on county death-row populations in 2001 was compiled by my intern, Rafi Rom, for my study, Racial composition of death row in the seventy most populous counties in states with the death penalty, July 16, 2001, conducted while I was Director of Training in the Capital Habeas Unit of the Federal Community Defender for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. Data on county death-row populations in 2021 are based on my calculations from the Death Penalty Information Center’s Death Penalty Census filtered by county. Other death-row population figures are from the cited issues of the Legal Defense Fund’s Death Row USA.

The Death Penalty Policy Project (“DP3”) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization housed within the Phillips Black Inc. public interest legal practice. DP3 provides information, analysis, and critical commentary on capital punishment and the role the death penalty plays in mass incarceration in the United States.