DP3 Analysis: Death Penalty States Are Weakest in Nation on Gun Safety

Data from Everytown for Gun Safety rebuts notion that capital punishment has value as an instrument of public safety.

A policy analysis by the Death Penalty Policy Project (DP3) has found that states with the death penalty tend to have the highest rates of death from gun violence and the weakest gun safety laws in the nation, while states that have abolished capital punishment or imposed moratoria on executions are leading public safety efforts to combat gun violence and have the lowest rates of gun-related deaths.

The analysis, which relied upon ratings of gun safety laws by the non-profit research and policy organization Everytown for Gun Safety,1 cross-referenced Everytown’s rankings of state gun safety laws and deaths from gun violence against each state’s death penalty status. The results showed that death penalty states both had more gun deaths and failed to undertake meaningful legislative steps to address gun violence.

Death penalty proponents have long claimed, without evidence, that capital punishment is a useful public safety tool. But the data actually suggest that states with the death penalty are more interested in talking tough about crime and imposing harsh punishment after the fact than they are about protecting the public in the first place. The states whose actions indicate that they are truly concerned about preventing gun violence don’t use the death penalty.

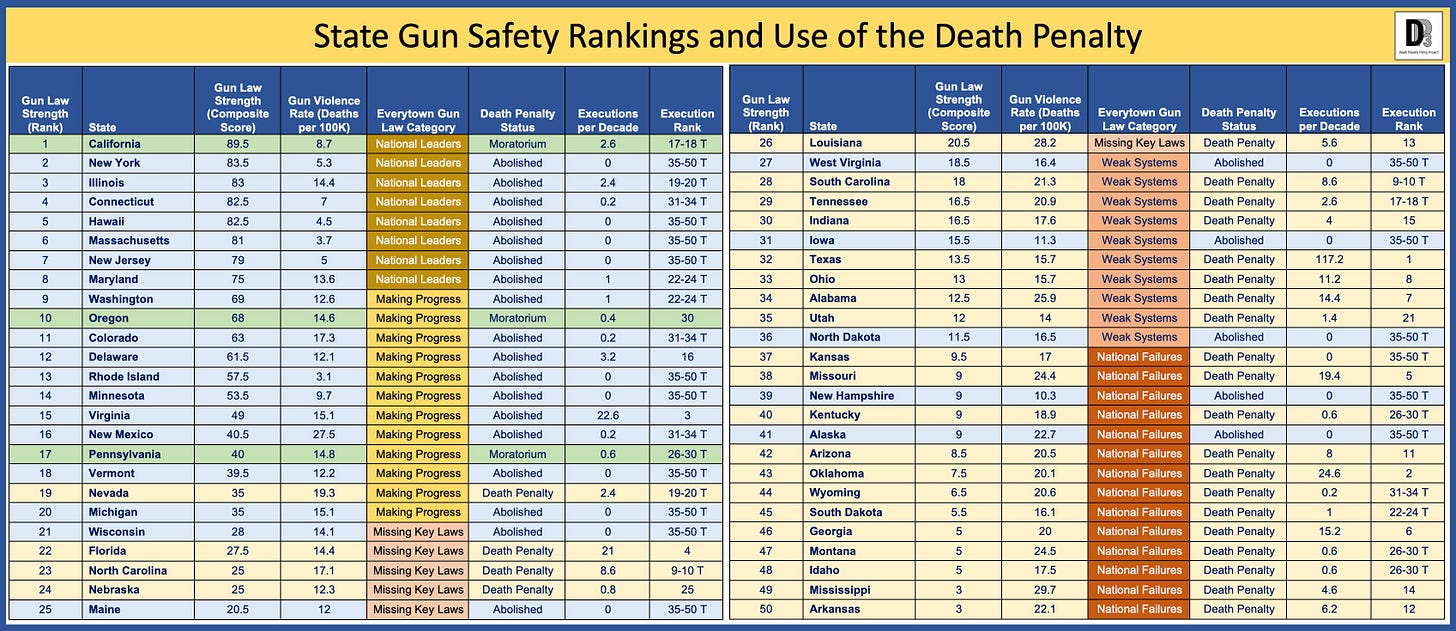

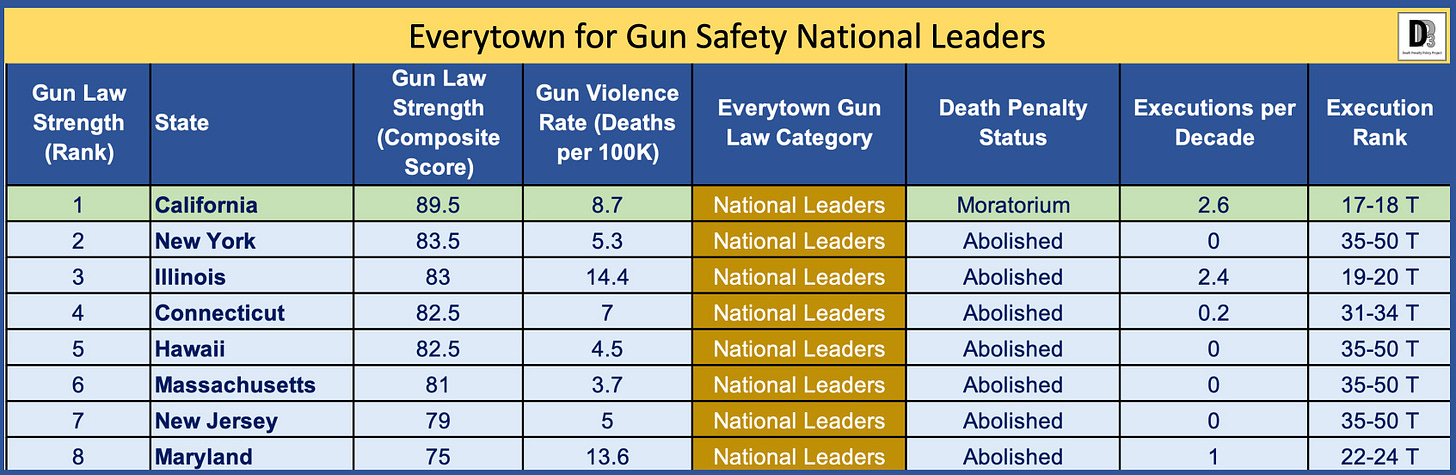

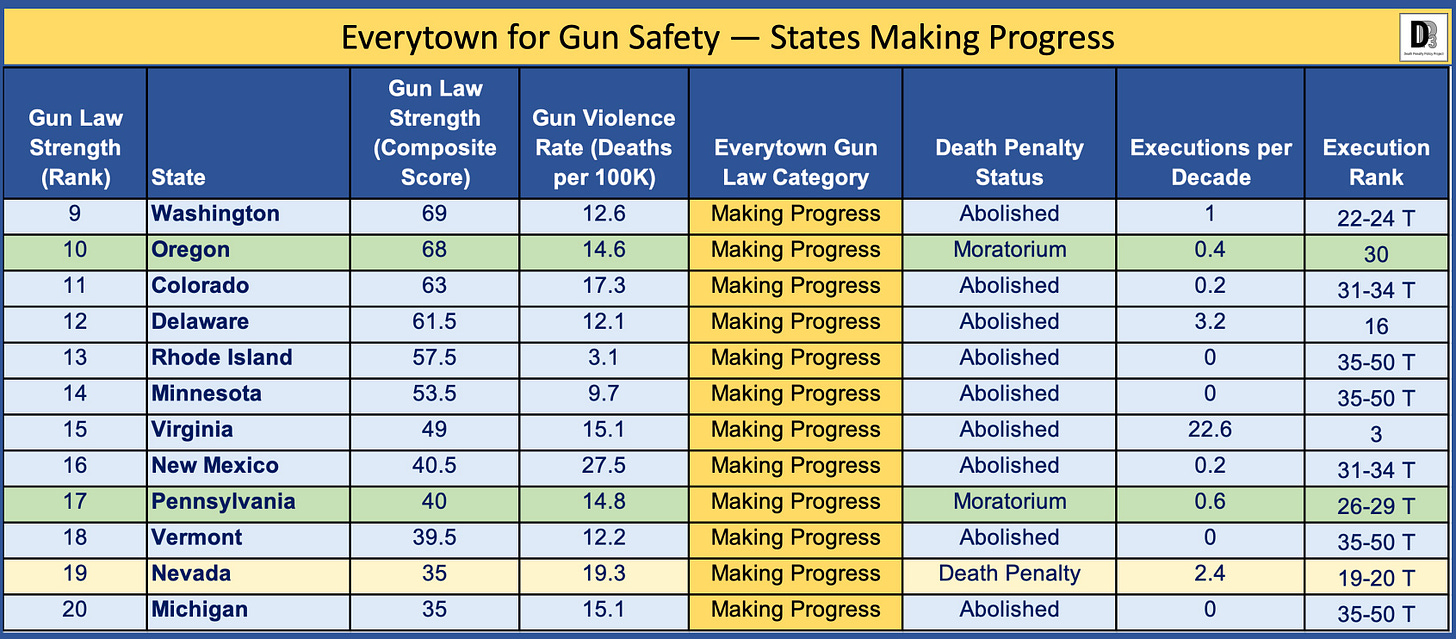

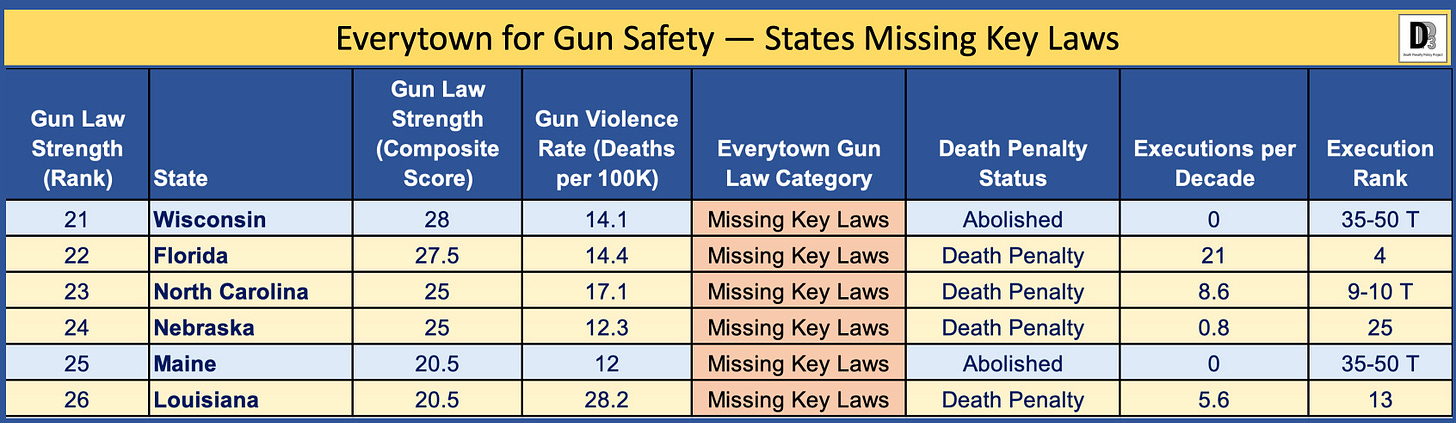

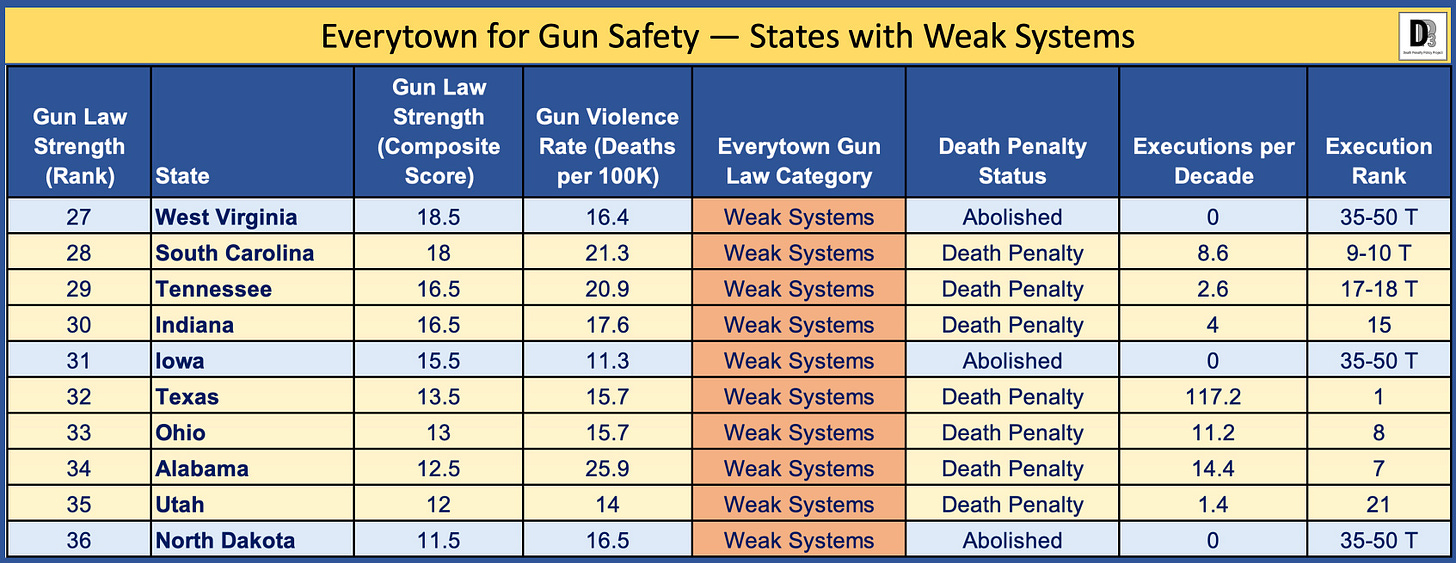

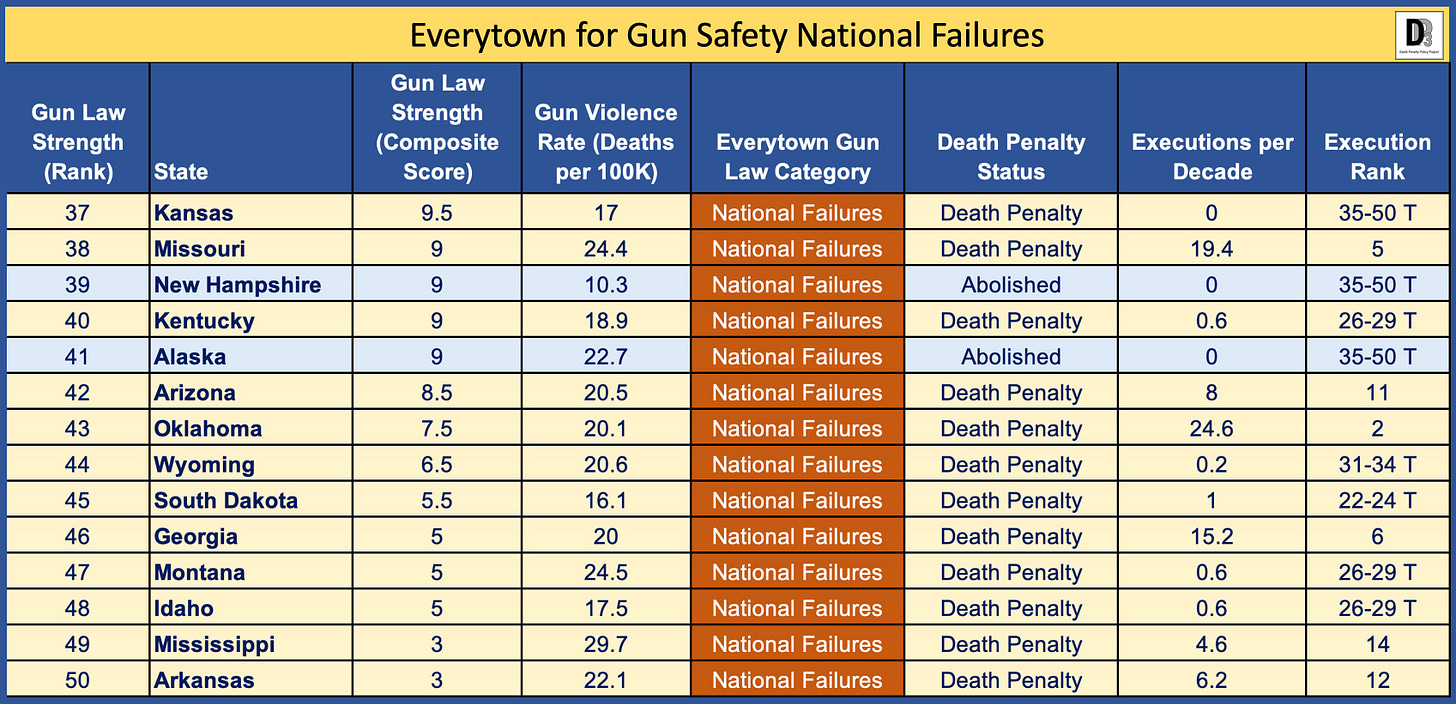

Everytown classified states into five categories based upon the strength of their gun safety laws: “national leaders,” “making progress,” “missing key laws,” “weak systems,” and “national failures.” All eight of the states Everytown classified as national leaders and eleven of the twelve states it classified as making progress had either abolished the death penalty or imposed formal moratoria on executions. By contrast, four of the six states Everytown identified as missing key gun safety laws, seven of the ten it classified as having weak gun safety systems, and twelve of the fourteen states it regarded as national failures in protecting the public against gun violence were death penalty states.

The eighteen states with the strongest gun safety laws all had either abolished the death penalty or imposed moratoria on executions. The nine states with the weakest gun safety laws all authorized the use of the death penalty.

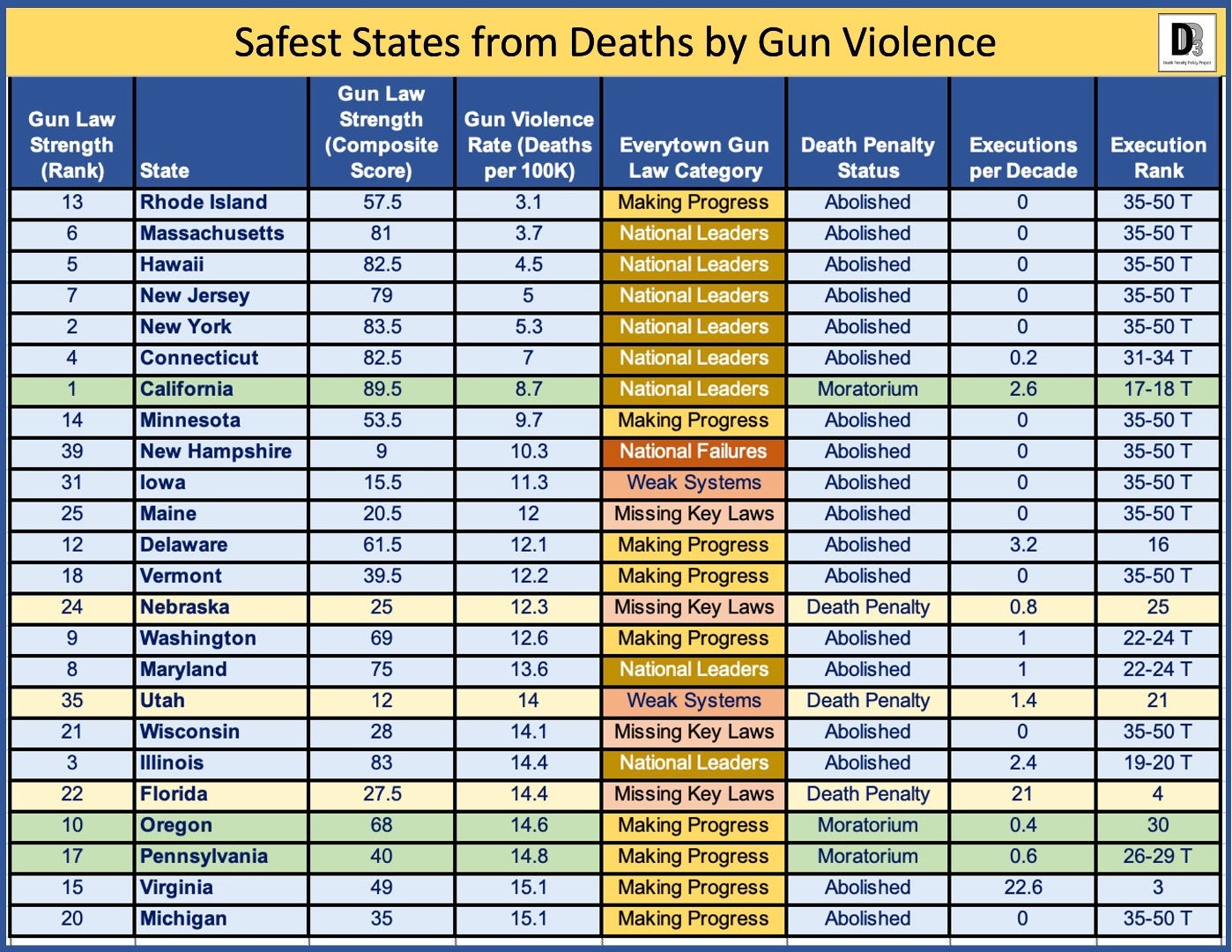

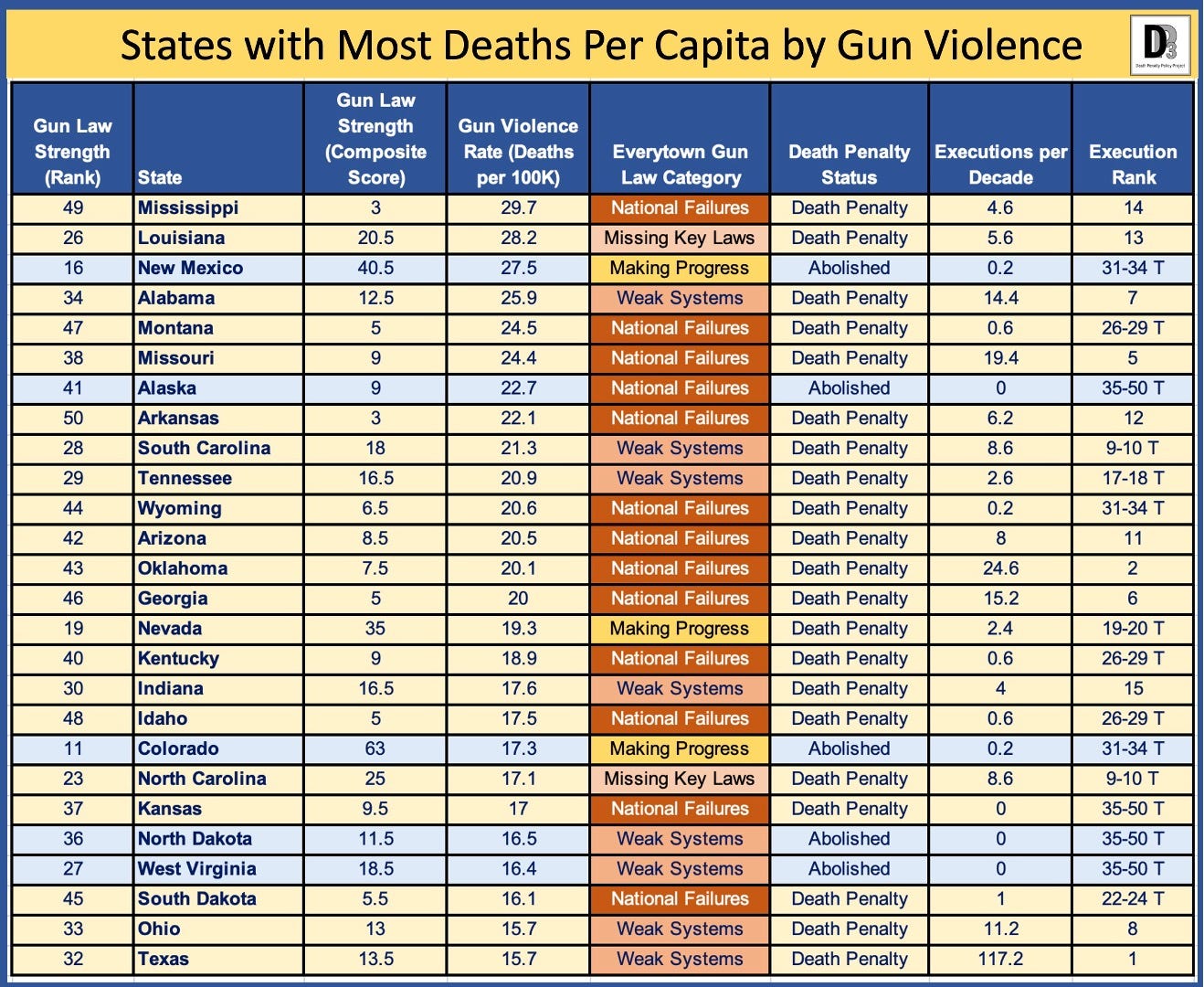

The data on gun violence showed that the thirteen safest states from death by gun violence and 21 of the safest 24 had either abolished the death penalty or imposed formal moratoria on executions, while sixteen of the eighteen states with the highest rates of deaths by gun violence, and 21 of the 26 most dangerous states were long-time death penalty states.

Everytown for Gun Safety reviewed state gun policies across the country, assessing the degree to which states had enacted fifty key gun policies. The organization scored and ranked each state according to the strength of its gun laws and then compared its gun safety laws with its rate of gun violence. Everytown found that “a clear pattern emerges” from its data: “States with strong laws see less gun violence. … [S]tates that have failed to put basic protections into place — ‘national failures’ on our scale — have a much higher rate of gun deaths than the national gun safety leaders.” In short, Everytown explained, “where elected officials have taken action to pass gun safety laws, fewer people die by gun violence.”

For years, evidence has been accumulating that undermines the myth that the availability of the death penalty contributes to public safety — a myth that experts in the field of public safety have long recognized is false. In 2008, a national poll of 500 police chiefs, commissioned by the Death Penalty Information Center, found that 57% of the chiefs believed that the death penalty “does little to prevent violent crimes.” Rather than serving a public safety function, 69% the chiefs said that “Politicians support the death penalty as a symbolic way to show they are tough on crime.” Results from a poll of leading criminologists published in the Winter 2009 issue of The Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology found that 88.2% of the criminologists did not believe that the death penalty is a deterrent. 90.9% of the criminologists agreed with the statement that “Politicians support the death penalty as a symbolic way to show they are tough on crime.”

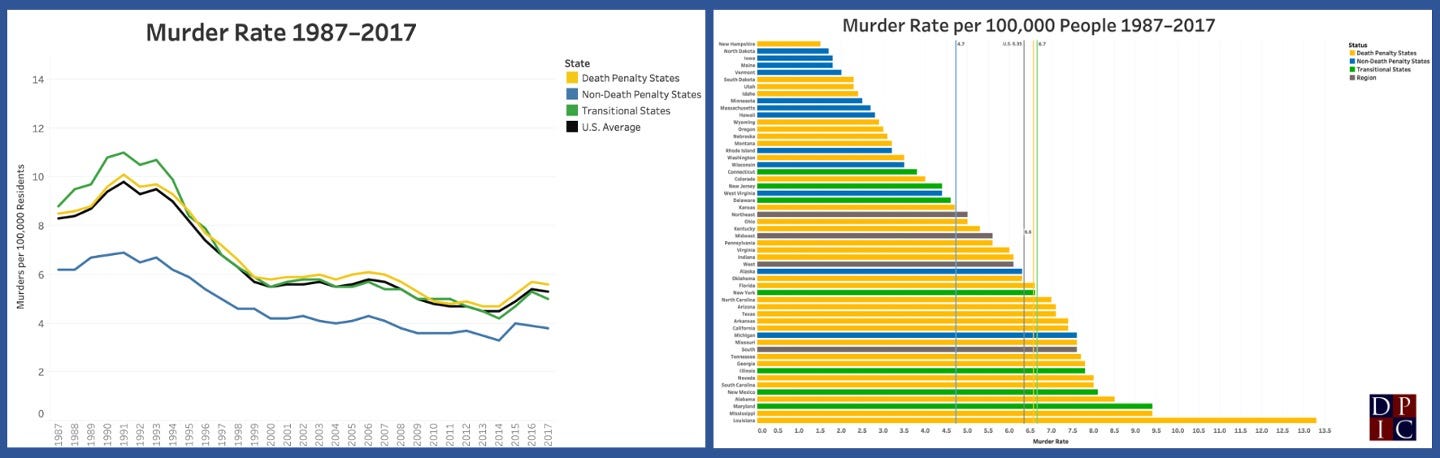

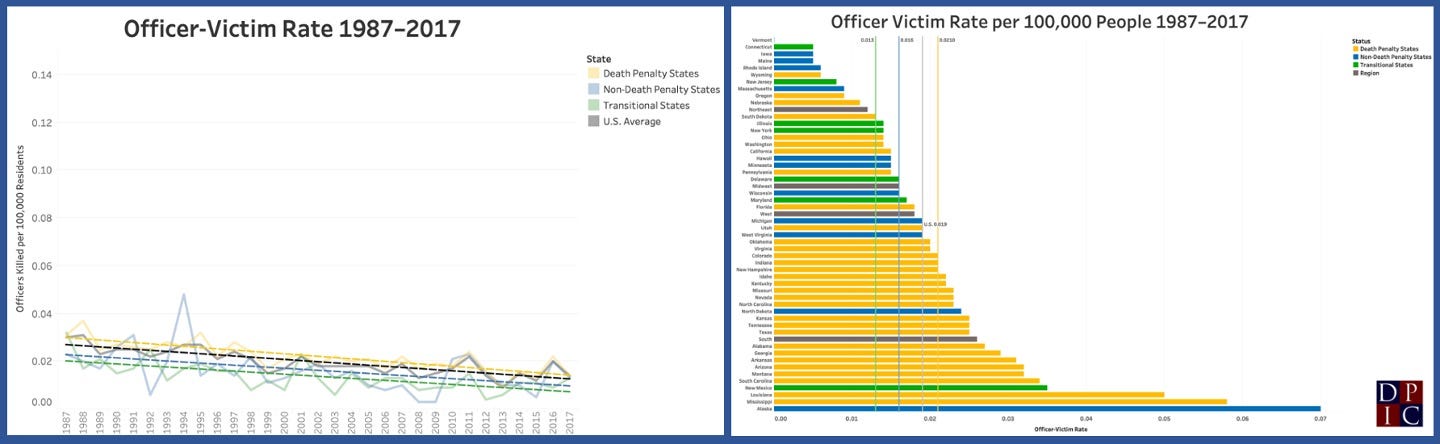

My review of thirty years of FBI homicide data while I was at DPIC, which I detailed in 2021 in testimony before a Wyoming state senate committee, found that the police and the public were safer in states that had abolished the death penalty than in death penalty states and that the presence or absence of the death penalty had no measurable impact on murder trends. We divided states into four categories: death penalty states; states that had never had the death penalty during any time in our study period (1987-2015, later expanded to 2017); transitional states that had abolished capital punishment at some point during the study period (all during the 21st century); and the nation as a whole. We found that murder rates, and the rates at which police officers were murdered, were consistently higher in death penalty states than in states that had abolished capital punishment; that the police and the public tended to be safest in states that had abolished the death penalty or used it the most infrequently; that murder trends were essentially the same, irrespective of a state’s death penalty status; and that murder rates, and the rates at which police were killed, did not rise — either in terms of raw numbers or in comparison to other states — after a state abolished the death penalty.

Figures 1-4 (top left to bottom right) — 1. Murder Rates 1987-2017 by State Death Penalty Status Death; 2. Murder Rates per 100,000 People by State; 3. Officer-Victim Murder Rates 1987-2017 by State Death Penalty Status Death; 4. Officer-Victim Murder Rates per 100,000 People by State. Death Penalty Information Center graphics by Patrick Geiger for testimony by Robert Dunham on March 4, 2021 in Hearings in the Wyoming State Senate Revenue Committee on SF 150 – Repealing the Death Penalty.

DP3’s analysis of the Everytown data provides additional evidence that the death penalty is not a tool of public safety, but is instead used most frequently by states that lack a commitment to addressing real public safety needs. While this is not true of every state, there tends to be an inverse relationship between gun safety and the death penalty: states with the death penalty tend to have the weakest gun safety laws and the highest rates of gun violence; states that have abolished the death penalty tend to have stricter gun safety laws and lower rates of gun violence.

DP3 compared the Everytown gun safety rankings to state death penalty status through several different lenses. First, we looked at death penalty status as a function of Everytown’s rating of the strength of a state’s gun safety laws. Then we compared death penalty status to a state’s rate of deaths from gun violence. Then we looked to see if there was any relationship between a state’s historical uses of the death penalty, as measured by the number of executions it performed in the past half-century, and its Everytown classification for gun safety. Viewed through any of these lenses, death penalty states showed a lesser commitment to public safety than states that had abolished capital punishment.

Gun Safety Laws — Strength of Law Rankings

Everytown ranked each state’s gun safety laws on a scale of up to 100 points, reviewing the presence or absence of 50 different safety policies. The organization weighted the value of each gun safety law based upon the policy’s impact on public safety, awarding the highest point totals for the presence of what Everytown deemed to be the “most fundamental laws” and lower point values to policies with what it considered to have “less substantial impact.” The laws were divided into four levels of descending importance, with up to six points awarded for policies requiring background check and/or purchase permits, “red flag” or “extreme risk” intervention laws, no “stand your ground” exceptions to prohibitions on shooting first, and requiring permits for concealed carry of firearms. States were awarded up to three points, up to 1.5 points, or up to one point for each additional gun safety law, depending upon the safety level of the policy.

The weaker the classification level was for gun safety, the more likely it was to be populated by death penalty states. The higher the gun safety designation, the more likely the category was to be populated by states that had either abolished the death penalty or formally imposed moratoria on executions.

National Leaders. The eight states designated by Everytown as “national leaders” in gun safety all have either abolished the death penalty or imposed moratoria on executions. Each had composite scores of 75 or above for the strength of their gun laws. California, rated by Everytown as having the nation’s strongest gun safety laws with a composite score of 89.5, has had a moratorium on executions since 2019 and has dismantled its execution chamber. The other seven states listed as national leaders are, in order of strength of their gun laws, New York (83.5), Illinois (83), Connecticut (82.5), Hawaii (82.5), Massachusetts (81), New Jersey (79), and Maryland (75).

Making Progress. Everytown classified twelve states with composite scores between 35 and 70 in the strength of their gun laws as “making progress.” Eleven of the twelve (91.7%) were death penalty abolitionist in law or practice. Washington, which judicially abolished its death penalty in 2018 and legislatively removed its capital punishment law from its statute books in 2023, had the strongest gun safety laws of this group of states, receiving a composite score of 69. The other eight abolitionist states in this category were Colorado (63), Delaware (61.5), Rhode Island (57.5), Minnesota (53.5), Virginia (49), New Mexico (40.5), Vermont (39.5), and Michigan (35). Everytown also considered Oregon (68) and Pennsylvania (40) — two states in which new governors extended existing moratoria on executions — to be making progress. Nevada, with a composite score of 35, was the lone non-moratorium death penalty state to be classified as making progress in its gun safety laws.

Missing Key Laws. Everytown classified states with composite strength of gun law scores in the twenties as “missing key laws.” Four of the six states in this category (66.7%) are death penalty states: Florida, with a composite gun safety score of 27.5, North Carolina and Nebraska (both at 25), and Louisiana (20.5). Two non-death-penalty states, Wisconsin (28) and Maine (20.5), also fell in this category.

Weak Systems. States with composite gun law strength scores between ten and twenty were classified as having “weak systems” for addressing gun violence. Ten states fell in this category, seventy percent of which had the death penalty. They are South Carolina (18), Tennessee (16.5%), Indiana (16.5), Texas (13.5), Ohio (13), Alabama (12.5), and Utah (12). Everytown also classified three death-penalty abolitionist states — West Virginia (18.5), Iowa (15.5), and North Dakota (11.5) — as having weak gun safety systems.

National Failures. Everytown classified fourteen states with scores below ten for gun law strength as “national failures.” Twelve of those states (85.7%) were death penalty states: Kansas (9.5), Missouri (9), Kentucky (9), Arizona (8.5), Oklahoma (7.5), Wyoming (6.5), South Dakota (5.5), Georgia (5), Montana (5), Idaho (5), Mississippi (3), and Arkansas (3). By contrast, only two abolitionist states — New Hampshire (9) and Alaska (9) — fell in this category. The nine states with the weakest gun safety systems were all death penalty states.

Gun Violence Rate — Gun Deaths Per 100,000 Residents

Everytown’s gun safety rankings also included each state’s gun violence rate, defined as the number of deaths from gun violence per 100,000 residents. The gun death rates were based on provisional 2022 age-adjusted figures from the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The data on gun violence showed a striking correlation between the death penalty status of a state and the rate of deaths from gun violence. The thirteen safest states from death by gun violence and 21 of the safest 24 states had either abolished the death penalty or imposed formal moratoria on executions. Sixteen of the eighteen states with the highest rates of deaths by gun violence and 21 of the 26 most dangerous states were long-time death penalty states.

States with More Executions Were Less Safe Than States with Fewer or No Executions

Contrary to what one would expect if the death penalty were a deterrent, increased frequency of executions did not make states safer from deaths by gun violence. None of the states with the 15 most executions in the past 50 years ranked among the nineteen safest states from deaths by gun violence. Yet eleven of those high execution states were among the 17 states with the highest rates of gun deaths. Texas, which averaged more than 100 executions per decade (more than five times greater than any other state), ranked 25th in per capita gun deaths with 15.7 gun deaths per 100,000 residents. Meanwhile, ten of the thirteen safest states have not executed anyone in the past half-century.

With few exceptions, the other high executing states ranked poorly in the prevention of gun deaths. Oklahoma, with an execution ranking of 2, was the 13th least safe state, with a per capita gun death rate of 20.1. Missouri, 5th in executions, was the 6th least safe state, with a per capita gun death rate of 24.4. Georgia, 6th in executions, 20 gun deaths per 100,000 residents, was the 14th least safe state. Alabama (7, 25.9) was the 4th least safe state; Ohio (8, 15.7), the 25th least safe; South Carolina (21.3) and North Carolina (17.1), tied for 9th in executions, were the 9th and 20th least safe states. Florida was the only high executing state (ranked no. 4) to rank among the top twenty (it was twentieth) in safety, with 14.4 gun deaths per 100,000 residents. Virginia, which ranked third in executions but has since abolished the death penalty, ranked 23rd in safety, with 15.1 gun deaths per 100,000 residents.

Death penalty states are much worse than other states in enacting gun safety legislation, including laws that have been proven to reduce gun deaths. Death penalty states have higher rates of gun deaths than almost every state that has abolished the death penalty. And states that execute more prisoners are more likely to experience more gun killings than states that have carried out fewer or no executions.

In short, fifty years of experience with capital punishment now tell us that the death penalty does nothing to address gun violence. It hasn’t made us safe. If anything, it has diverted resources and attention away from public safety policies that will work.

Everytown for Gun Safety was not consulted about or otherwise involved in this analysis. The opinions and conclusions expressed herein are solely those of the Death Penalty Policy Project.

The Death Penalty Policy Project (“DP3”) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization housed within the Phillips Black Inc. public interest legal practice. DP3 provides information, analysis, and critical commentary on capital punishment and the role the death penalty plays in mass incarceration in the United States.