DP3 Analysis: The Death Penalty Does Not Deter Mass Shootings

80% of the Deadliest U.S. Mass Shootings Were Committed in Death-Penalty Jurisdictions and Accounted for 84% of the Deaths from the Worst of the Worst Shootings

The defense had just moved to bar the death penalty in the federal trial in the Tops supermarket shooting in Buffalo, New York and the Sandy Hook elementary school children had just graduated from high school in Newtown, Connecticut.

Appeals were underway from the federal death penalty verdict in the Tree of Life Synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and multiple death penalty proceedings were crowding the courts in Florida after the life verdict in the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School mass shooting led the state legislature, responding to a fit of gubernatorial pique, to enact the lowest threshold in the nation for imposing the death penalty in any capital eligible crimes.

It was June 24, 2024. The headline read: “Mass shootings across the US mark the first weekend of summer.”

The threat of judicial punishment had failed to deter any of these attacks.

Fewer than 1% of gun deaths in the United States are a product of mass shootings, but mass shootings are, by definition, the deadliest and receive the most media attention. When the shooter survives, media coverage reflexively focuses on whether the perpetrator faces or will receive the death penalty and on calls by public officials demanding the ultimate punishment. The process of meting out punishment, rather than policy steps that can be taken to prevent mass shootings or mitigate the deadliness of those attacks, becomes the dominant and recurring theme of subsequent coverage.

With that in mind, the Death Penalty Policy Project analyzed available data on mass shootings to see what the relationship is between where the deadliest U.S. mass shootings have taken place and whether the jurisdictions in which they took place have or don’t have the death penalty. DP3’s analysis of the data exposes the notion that the death penalty is a deterrent to mass shootings as a false and dangerous fantasy.

A prior Death Penalty Policy Project analysis in January 2024 found that the death penalty is a public safety policy failure when it comes to gun violence in general. As a group, states with the death penalty have higher rates of death from gun violence than states that have abolished capital punishment. And among death penalty jurisdictions, states with the most executions tend to have much higher rates of deaths from gun violence than do states with formal moratoria on executions or that permit executions but rarely carry them out.

If the most extreme punishment available in the U.S. legal system made no discernible contribution to public safety when it comes to gun deaths in general, is it possible that it could nevertheless be a valuable deterrent against the worst of the worst shootings?

To find out, DP3 looked to data compiled by the Gun Violence Archive (GVA), an independent non-profit data collection and research organization created in 2013 to, in its own words, “provide free online public access to accurate information about gun-related violence in the United States.” GVA compiles information on gun violence from more than 7,500 law enforcement, media, government and commercial sources “to document incidents of gun violence and gun crime nationally [and] provide independent, verified data to those who need to use it in their research, advocacy or writing.” According to its mission statement, “GVA is not, by design, an advocacy group.”

DP3 examined every mass shooting in the past fifty years in which ten or more people other than the shooter were killed and compared the death-penalty status of the locations in which the shootings occurred to assess whether, and to what extent, the threat of capital punishment has prevented the most significant carnage from taking place. We found that, since the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the death penalty in 1976, 80% of those mass shootings have taken place in death penalty states or on federal property subject to the federal death penalty.

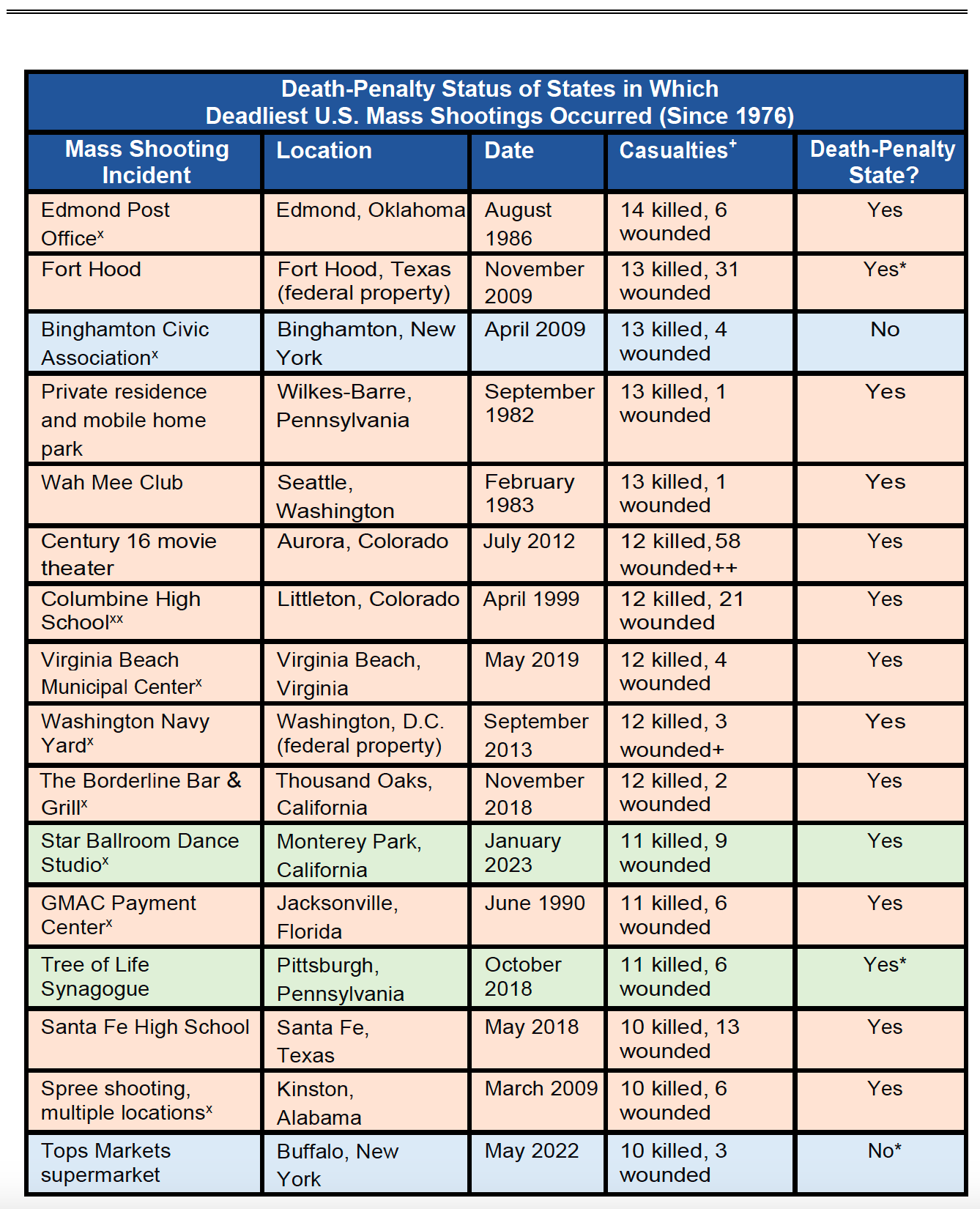

Table 1, above, displays mass shootings in order of the number of victims killed and wounded. Mass shootings that took place in states with active death penalty statutes are depicted in pale orange, mass shootings in death-penalty states while execution moratoria were in place in pale green, and mass shootings in states that had abolished the death penalty in pale blue. The Gun Violence Archive casualty data includes only victims who were shot. Those who sustained injuries from other causes during the course of escaping the shooting are not included in the figures.

If we limit the review to the deadliest 25 mass shootings — an admittedly arbitrary distinction given the fortuity of whether a victim survives or is killed in these attacks — 88.0% occurred in death penalty jurisdictions. Similarly, eight of the nine mass shootings in which 20 or more people were killed (88.9%) took place in death penalty states.

Twenty-four of the 30 mass shootings in which ten or more victims were killed occurred in death penalty states or on federal civilian or military property. Twenty-two took place in states where the death penalty was active at the time; two others in states in which governors had imposed moratoria on executions but local prosecutors were still free to seek the death penalty. The other six mass shootings in which ten or more victims were killed took place in non-death penalty states or former death penalty states that had recently abolished capital punishment.

But even this data understates the availability of the death penalty as a punishment for the mass killings and its failure to deter them. The Pittsburgh Tree of Life Synagogue killings took place after Pennsylvania had imposed a moratorium on executions. Though the shooter was still subject to potential state capital prosecution, federal prosecutors sought and obtained the death penalty in that case. The perpetrator in the Tops Supermarket shootings in Buffalo did not face the death penalty under New York law but is being capitally prosecuted by the federal government. If the Tops shooting is included as occurring in a death penalty jurisdiction, then 83.3% of the nation’s worst mass killings were not deterred by an available death penalty.

The worst of the worst mass shootings took place in fourteen different jurisdictions (thirteen states and on federal property in the District of Columbia). See Table 2, below. Eleven of those jurisdictions (78.6%) authorized the death penalty at the time of the mass shooting —Alabama, California, Colorado, Florida, Nevada, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia, Washington state, and the federal government. Colorado had two mass shootings with ten or more fatalities while it had the death penalty and has had a third such shooting after abolition. Three other non-death-penalty states — Connecticut, Maine, and New York — have had mass shootings with ten or more fatalities.

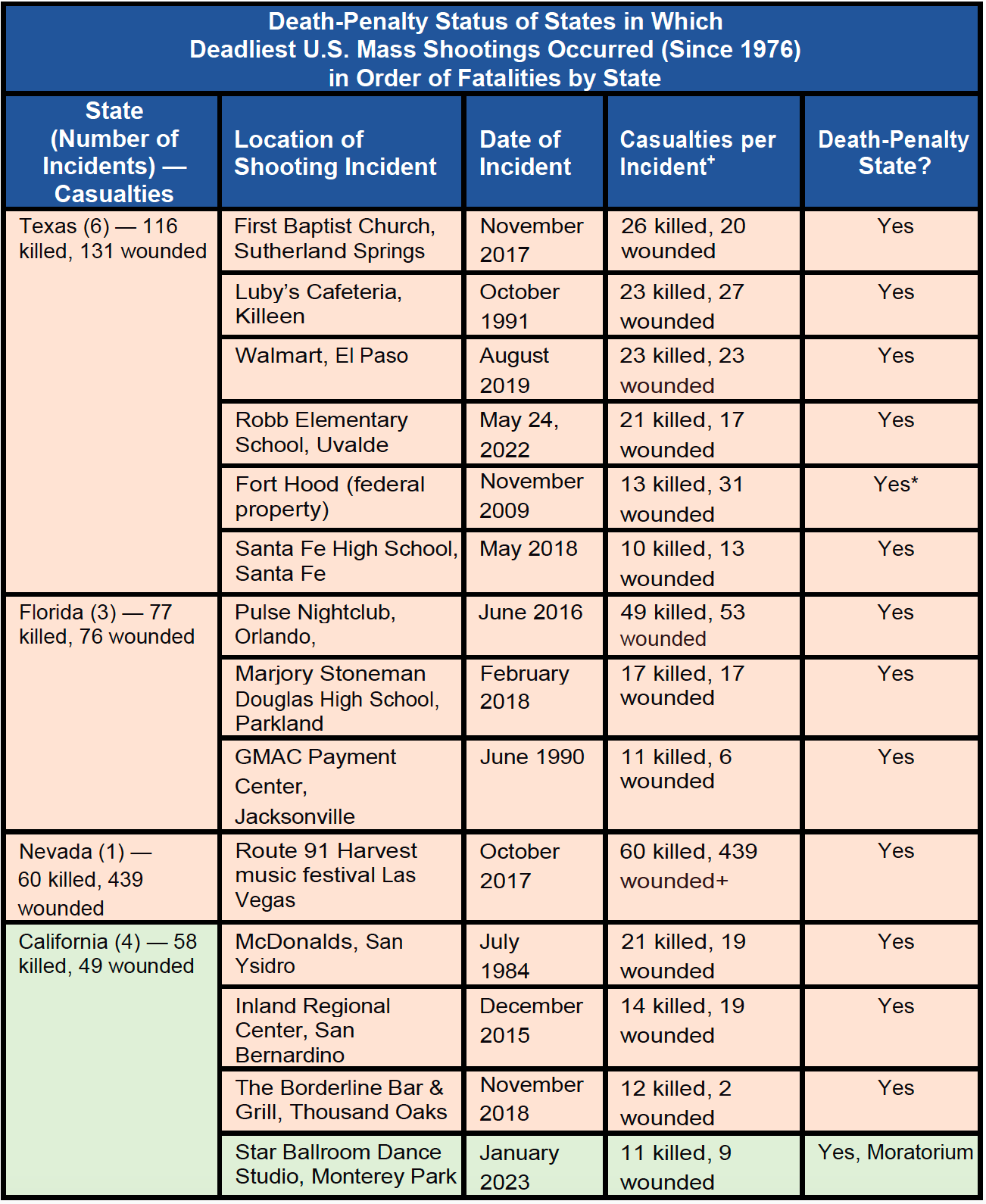

Seven states have had multiple incidents in which ten or more victims were killed in mass shootings. Texas has had six such incidents; California, four; Colorado, Florida, and New York, three each; and Pennsylvania and Virginia, two each. Six of the seven states (85.7%) had multiple mass shootings with 10+ fatalities despite authorizing the death penalty at the time. New York was the only non-death-penalty state with multiple mass shootings in which ten or more victims were killed.

Even considering the heavy casualties in the Sandy Hook elementary school shooting (27 killed, 2 more wounded), the worst of the worst mass shootings in the U.S. have been deadlier in death penalty states. The six mass shootings in Texas that have killed ten or more people have collectively left 116 dead and another 131 wounded. In Florida, three mass shootings have killed 77 and wounded another 76. The music festival massacre in Las Vegas, Nevada killed 60 and wounded 439. California’s four incidents have killed 58 and wounded 49. The three mass shootings with ten or more fatalities that occurred before there was a moratorium on executions in the state left 47 victims dead and wounded 40 others. The mass shootings at on the campus of Virginia Tech and at the Virginia Beach Municipal Center killed 44 and wounded 21.

Collectively, the thirty mass shootings that have resulted in ten or more deaths have taken the lives of 540 people and wounded 840 others. (Table 3.) 452 of those who were killed (83.7%) and 818 of those who were wounded but survived (97.4%) were shot in death-penalty jurisdictions. The worst of the worst mass shootings in death-penalty jurisdictions took an average of 18.8 lives and wounded an average of 34.1 people. Excluding the mass shootings that took place in death-penalty states while execution moratoria were in effect, those averages rise to 19.5 killed and 36.5 wounded.

In contrast, the six of the nation’s worst of the worst mass shootings that took place in jurisdictions with no death penalty resulted in 88 deaths (an average of 14.7 per shooting), with an additional 22 people wounded (an average of 3.7 per shooting).

The relatively small sample sizes and the statistical skewing effects of incidents such as the Las Vegas music festival shooting make meaningful numerical comparison difficult. But the numbers clearly show that the worst of the worst mass shootings in the U.S. have occurred more often and have been more deadly in states that have the death penalty.

Why the Death Penalty Does Not Deter Mass Shootings

The death penalty has not deterred mass shootings, nor can it. The rational assessment of consequences assumed by deterrence theory simply doesn’t apply to these crimes.

DP3 looked at expert commentary on the Violence Project Mass Shooter Database to explain why. The Mass Shooter Database has collected data from open sources on nearly 200 mass shootings in the United States since 1966. The database, which is housed at the Violence Prevention Project Resource Center at Hamline University, was compiled with support from the Department of Justice’s National Institute of Justice. Its aim, according to the Violence Project website, “is to build a broader understanding on the part of the public, the justice system, and the research community of who mass shooters are and what motivates their decision to discharge firearms at multiple people.”

The data show that a majority of mass shooters are suicidal, “commonly troubled by personal trauma before their shooting incidents [and] nearly always in a state of crisis at the time.”1 The Hamline University researchers describe mass shootings as “public spectacles of violence intended as final acts.” They say that whether death is “self-inflicted, or comes at the hands of police officers, or after [judicial punishment], a mass shooting is a form of suicide.”

According to the database, 31% of mass shooters were suicidal prior to committing the mass killing and another 40% were suicidal while they were carrying it out. And as NIJ points out, these numbers “were significantly higher for younger shooters.” 92% of high-school-aged or younger perpetrators of mass school shootings were suicidal, as was every college or university student who committed a mass school shooting.

For a potential mass shooter who is suicidal, the threat of judicial execution is not a deterrent. But mass shootings typically never get to that point. NIJ notes that “[m]ost [shooters] died on the scene of the public mass shooting, with 38.4% dying by their own hand and 20.3% killed by law enforcement officers.” That’s 58.7% of all mass shootings.

DP3’s review of the 30 deadliest mass shootings in the past half-century found that the on-the-scene death toll for the shooters in those cases was even higher. 63.3% (19 of 30) of the individuals who committed the worst-of-the-worst mass killings did not survive to be arrested, including the shooters in nine of the ten deadliest incidents. (See Table 1.)

Other factors underscore the ubiquity of mental health issues that make belief in judicial deterrence a fantasy in mass shooting cases. The data indicate that 30% of the shooters were affected by psychosis at the time of the killings. Psychotic thought or perception played a “major role” in 10.5% of the mass shootings and a lesser, but nevertheless contributing, role in another 19.7% of the shootings.2

Moreover, as NIJ explains, “nearly all persons who engage in mass shootings were in state of crisis in the days or weeks preceding the shooting.” The latest findings from the Violence Prevention Project Resource Center indicate that 80% of mass shooters “were in a noticeable crisis prior to their crimes.” The signs of crisis included increased agitation (66.9%), abusive behavior (41.9%), isolation (39.5%), losing touch with reality (33.1%), depressed mood (29.7%), mood swings (27.3%), inability to perform daily tasks (24.4%), and paranoia (23.8%). 43.15% of mass shooters “exhibited between one and four crisis signs,” the Violence Prevention Project notes, and “more than a third of shooters [37.7%] showed five or more crisis signs.”

It seems absurd to even have to say it out loud, but individuals who are in the throes of emotional crisis are not engaging in the rational assessment of consequences required for a deterrent to deter. It is even more absurd to believe that they are consulting the punishments provided in a state’s criminal code to guide their conduct.

Instead of deterring violence, the death penalty may actually make the problem of mass shootings worse.

A significant number of mass shooters — 21.6% according to the Violence Project database — study past mass shooters. Many, NIJ says, are radicalized online. And the Harmelin researchers have noticed a disturbing new development: “shootings motivated by hate and fame-seeking have increased since 2015.” The sensationalized publicity surrounding the decision whether a mass shooting case becomes a death penalty case, and the supercharged true crime coverage the trial then receives becomes part of the radicalizing and fame-seeking on-line environment.

So, while the death penalty does nothing to prevent mass shootings, it may play an indirect role in causing them. The way society sensationalizes high profile death penalty cases confers upon the mass shooter a notoriety another at-risk individual in emotional crisis may crave, and that may, in turn, contribute to that person’s decision to attempt a mass shooting.

Finally, the politics of punishment is the politics of diversion. Attention and resources directed to post-offense retribution is attention and resources diverted from programs and policies that can make the public safer.

What Policies Might Prevent Mass Shootings or Make Them Less Lethal?

No one who cares about saving innocent lives by preventing even a single mass shooting believes that the death penalty should have a seat at the policy table. The death penalty does nothing to keep deadly weapons out of the hands of potential offenders or to deter people with those weapons from committing mass shootings.

But there are evidence-based policies that can help to prevent mass shootings and make the ones that do happen less lethal. The non-profit research and policy organization Everytown for Gun Safety has proposed a series of common sense public safety policies that have proven histories of making a difference. These include requiring background checks on all gun sales, enacting “extreme risk” or “red flag” laws that remove guns from people who show warning signs of violence, prohibiting people with dangerous histories (including hate-crimes convictions) from having guns, and prohibiting assault weapons, high-capacity magazines, and rapid-fire conversion devices such as bump stocks.3

The prohibition on automatic high-powered weaponry is perhaps the most important step that can be taken to reduce the death toll from mass shootings. Mass shootings in which four or more people are killed are much more lethal when the shooter uses an assault rifle. In those incidents, the death toll is an average of 2.3 times greater and an average of 22.7 times more people are wounded.

The same is true of mass shootings in which the killer employs high-capacity magazines. In mass shooting incidents in which the magazine type was known, Everytown found that 2.5 times more people were killed and there were nearly 10 times more casualties overall when high-capacity magazines were involved.

Everytown researched the weaponry used in the ten deadliest mass shootings in the U.S. since 2016 and was able to identify the type of gun used and the magazine type present in nine of those shootings. Eight of these nine mass shootings (88.9%) involved an assault weapon, and the shooters in eight of the nine incidents used high capacity magazines.4

What is the bottom line? The death penalty has not deterred and cannot prevent mass shootings. Its continued use is a harmful diversion of attention and resources from policies that can.

National Institute of Justice, Public Mass Shootings: Database Amasses Details of a Half Century of U.S. Mass Shootings with Firearms, Generating Psychosocial Histories (Feb. 3, 2022).

The Violence Project, Key Findings (webpage last visited July 21, 2024).

Everytown for Gun Safety, Mass Shootings (webpage last visited July 21, 2024).

Everytown for Gun Safety, Mass Shootings in the United States (last updated March 2023).

The Death Penalty Policy Project (“DP3”) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization housed within the Phillips Black Inc. public interest legal practice. DP3 provides information, analysis, and critical commentary on capital punishment and the role the death penalty plays in mass incarceration in the United States.