DP3 Testimony on Bill to Abolish Ohio's Death Penalty

Death Penalty Policy Project Director Robert Dunham testified before the Ohio Senate Judiciary Committee on December 4, 2024

Introduction

Good morning, Chairman Manning, Members of the Committee. My name is Robert Dunham. I am the Director of the Death Penalty Policy Project and former Executive Director of the Death Penalty Information Center. I want to thank the Committee for providing me this opportunity to speak with you to assist in your deliberations on Senate Bill 101, to prospectively abolish Ohio’s death penalty.

Before moving to the policy arena, I served for twenty years in capital defender organizations, as executive director of the Pennsylvania Capital Case Resource Center, Director of Training in the capital habeas unit of the Philadelphia federal defenders office, and as an assistant federal defender in the capital habeas unit of the Federal Defender Office for the Middle District of Pennsylvania. During that time, I represented death-sentenced clients in Pennsylvania’s state and federal courts, including arguing in the U.S. Supreme Court, and was part of the legal teams that helped to exonerate four innocent death-row prisoners and had another innocent death-row client die in prison before he could be exonerated.

In addition to my work at the Death Penalty Policy Project, I am a member of the Board of Directors of Witness to Innocence, a national organization of U.S. death-row exonerees; special counsel in the national non-profit legal practice at Phillips Black, Inc.; and teach death penalty law at the Temple University Beasley School of Law.

Two weeks ago, I had the privilege of accompanying former Irish Prime Minister Enda Kenney and former Connecticut Governor Dannel Malloy, along with the co-directors of the International Commission Against the Death Penalty, to meet with many of you regarding your concerns about capital punishment. You have heard from numerous witnesses in earlier hearings on this bill, and I don’t want to burden you with rehashing the issues they’ve already addressed. You have already formed deeply held beliefs about the sanctity and dignity of human life and whether it is ever appropriate for the government to exercise the awesome and intrusive power to take a life. You also already have heard about the dozens of cost studies that show that a system of justice that employs the death penalty is far more costly and error prone than a system of justice in which life without parole or a long term in prison is the harshest punishment.

Instead, what I would like to address today are the questions you and your colleagues raised during our meetings two weeks ago. Does the death penalty make the public safer? Does it protect police? What is its impact on victims’ families? Is it necessary as a “stick” or a “bargaining chip” to resolve cases with guilty pleas that potentially eliminate years of appeals? Aren’t some crimes just so horrible that no other penalty will do?

I. After 1,600 Executions, the Public and Law Enforcement Personnel Are Safer in States that Don’t Have tbe Death Penalty than in States that Do.

Let me start with public safety. If the death penalty makes the public safer, that is an important reason to keep it. And if the death penalty protects police, that is a strong argument to retain it, at least for that limited class of murders. But does it actually do that? If we want public policies that work and if we don’t want excessively harsh policies that don’t make us safer, that’s certainly something we should want to know.

With that in mind, the Death Penalty Policy Project analyzed more than three decades of FBI homicide data and FBI data on law enforcement officers killed in the line of duty.1 Now, if capital punishment serves a public safety purpose, states that have and states that use the death penalty should, as a group, have comparatively lower murder rates and comparatively fewer killings of police officers in the line of duty than states that don’t authorize capital punishment and than states that have the death penalty on the books but don’t carry it out. In addition, if the death penalty has special protective value for police officers, killings of law enforcement in the line of duty should constitute a comparatively smaller percentage of murders in death penalty states than they do in abolitionist states.

That, at least, is what the theory of deterrence tells us.

But that’s not what the data tell us. Instead, we found that fifty years into the modern death penalty in the United States, after 1,600 executions, the public and police are actually safer in states that don’t have or have recently abolished the death penalty. And, among the death penalty states, the public and police are safer in states that currently have official moratoria on executions or have rarely executed anyone.

Moreover, the states that are now most actively carrying out executions are among the least safe for the public and the most dangerous for police. They have failed to execute their way into violence prevention. The data also corroborate an important preliminary finding from an earlier version of this study conducted when I was at the Death Penalty Information Center: murder rates don’t rise and police are not put in danger when states abolish the death penalty.2

I’ve described the study in greater detail in an analysis that I posted on the the Death Penalty Policy Project’s DP3 Substack.3 But here are some highlights:

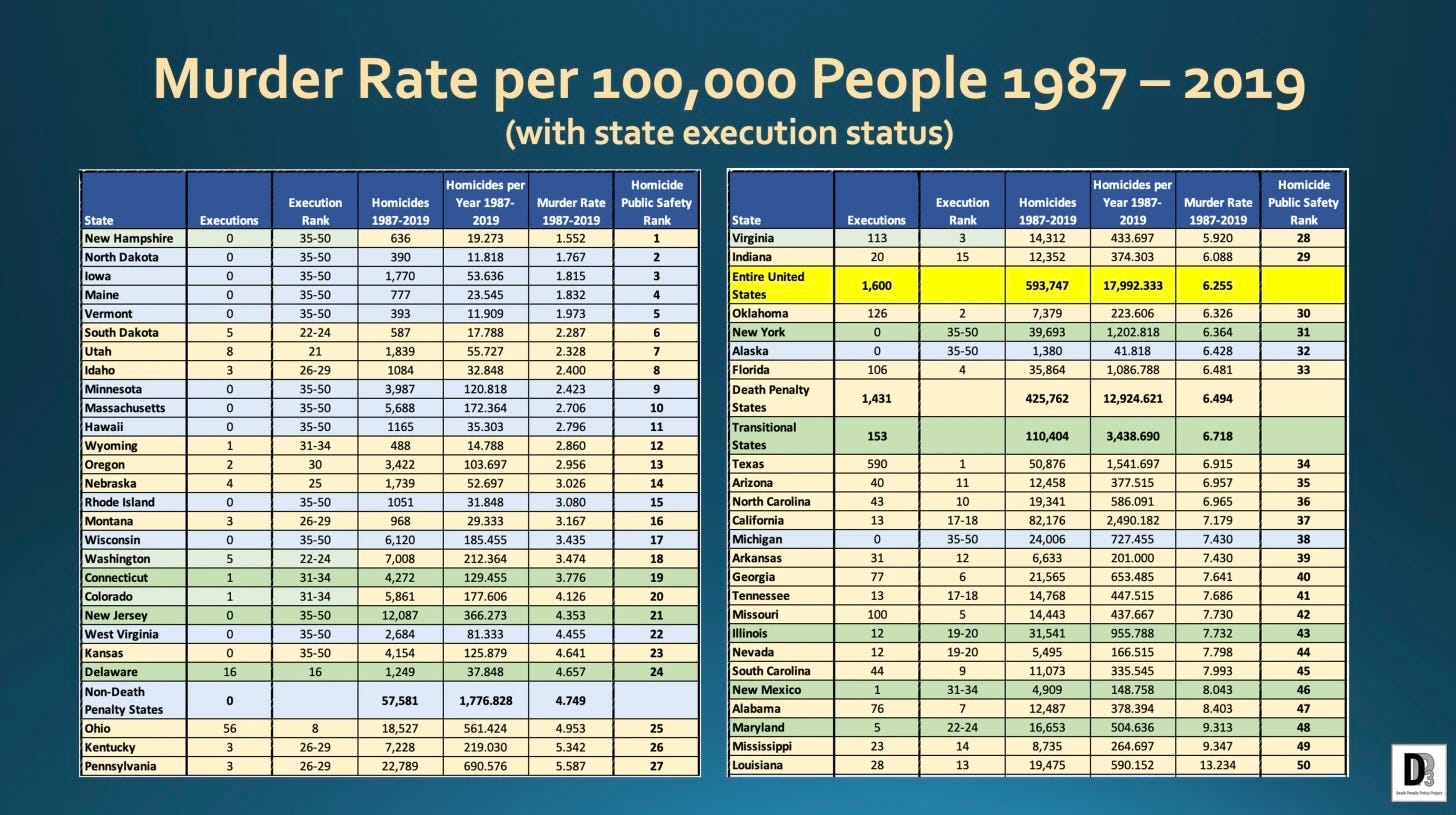

A. States With No Death Penalty Had the Lowest Murder Rates

First, as a group, states that never had the death penalty at any time during the 33 years we studied had by far the lowest murder rates: 4.749 murders per 100,000 population, compared to 6.494 for death penalty states and 6.255 for the United States as a whole. Their collective murder rate was 37% lower than that of the states that had the death penalty for all 33 years of the study, and it was 32% lower than the murder rate in the U.S. as a whole.

Moreover, the public was consistently safer in states that didn’t have the death penalty. In each of the 33 years covered by the stady, the murder rate in the non-death penalty states was below the national average and the murder rate in the death penalty states was above the national average.

To make sure this was not some statistical aberration caused by lumping states together as a class, we then looked at the states individually. What we found was that the safest states either didn’t have or didn’t use the death penalty. All 24 states with the lowest murder rates had either abolished the death penalty, had no one on death row, or had averaged no more than one execution per decade since the 1960s. By contrast, 92% of the states with murder rates placing them in the bottom half of the nation in public safety had been death penalty states for most or all of the study period.

And executions didn’t make the public safer. Seven states account for 75% of the executions conducted by states in the past fifty years. Their comparatively high murder rates place all of them in the bottom half of states in public safety. In fact, six of them ranked 30th or below in public safety and two ranked 40th or below.

The DP3 homicide study also provided important information about whether abolishing the death penalty endangers public safety. It doesn’t.

To analyze this, we looked at murder rates in the “transitional states” — states that had the death penalty but abolished it during the study period. We are in the process of conducting a more extensive analysis of these states, but some facts are clear. Abolishing the death penalty did not produce any distinctive pattern of change in homicide rates: there was no “abolition effect.” Post-abolition homicide trends appeared to reflect national trends. But importantly, homicide rates did not spike following abolition. The surge in murders predicted by the deterrence hypothesis never materialized. Abolishing the death penalty did not adversely affect public safety.

B. Police Were Least Safe in States With the Death Penalty

Second, the FBI data on law enforcement personnel killed in the line of duty show that having the death penalty has not made officers safer. Over the course of the 33-year period we analyzed, law enforcement officers were disproportionately killed in the line of duty in states that had the death penalty, as compared to states that didn’t. Police were the least safe in death penalty states and, paradoxically, the safest in states that had most recently abolished capital punishment.

Police officers in death penalty states were murdered at a rate 1.11 times higher than the national average. By contrast, the officer-victim murder rate in non-death penalty states was 36% lower than in the death penalty states. That police face such a significantly greater risk of being murdered in long-time death penalty states than in states that don’t authorize capital punishment obliterates any argument that the death penalty promotes — let alone is necessary for — officer safety.

Even more interestingly — and impossible to explain if the death penalty contributes to law enforcement safety — officers were by far the safest in states that had previously authorized capital punishment but had recently abolished it. In these transitional states, the officer-victim murder rate was 61% lower than in the long-term death penalty states and 44% lower than the national officer-victim murder rate.

Defying the deterrence hypothesis, the rates at which police officers are killed was higher most years in states that have the death penalty than in states that don’t. It also was lowest most years in transitional states that once had the death penalty but later abolished it. Again defying the deterrence hypothesis, murders of police remained significantly lower in the transitional states than in the other death penalty states even after the transitional states abolished the death penalty.

Thankfully, killings of police in the line of duty are very rare. However, because of this, the year-to-year numbers are volatile. To control for this, we generated trend lines for each of the categories of state death-penalty status. The trends confirmed that police were safest in states that would eventually abolish the death penalty, then in states with no death penalty, and were least safe in states that had and kept capital punishment.

When we broke down the data state-by-state and ranked the states by officer safety, the gap between the safety of officers in death penalty retentionist states and in states that never had or later abolished the death penalty was even more dramatic.

Seven of the nine safest states for law enforcement don’t have the death penalty and the two that do don’t have anyone on death row. Of the safest 27 states, 19 don’t have the death penalty. Conversely, nineteen of the 23 most dangerous states for law enforcement are death penalty states, including 12 of the 15 states that have carried out the most executions in the U.S. since 1976. The seven safest death penalty states for police don’t use it: four either have formal moratoria on executions or no one on death row.

Having the death penalty and carrying out executions do not make police safer.

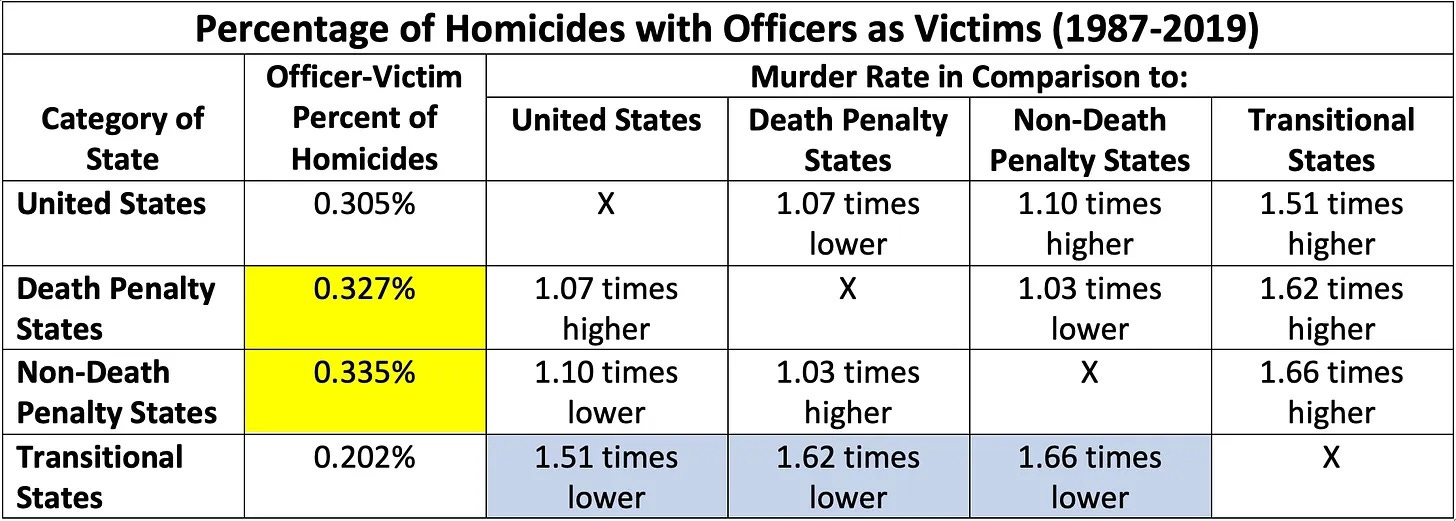

C. States that had Most Recently Abolished the Death Penalty had the Lowest Percentage of Murders Involving Officer Victims

If the death penalty has special value in protecting police, murders in which police are victims should comprise a smaller percentage of all murders in states that have the death penalty than in states that don’t. But it turns out that there is virtually no difference (eight one-thousandths of a percent) in the percentages between death penalty states and non-death-penalty. On the other hand, the percentage of murders with officers as victims is substantially lower in the transitional states — 51% below the national average and more than 60% below the averages for both the death penalty and non-death penalty states.

A state-by-state analysis of officer-victim murders as a percentage of all homicides dramatically illustrates the inverse relationship between death penalty usage and the relative safety of police officers. The states in which police were comparatively the safest were states that had most recently abolished the death penalty, didn’t have the death penalty, or had a death penalty but didn’t use it.

None of these data make sense from a deterrence perspective. Why should a state that once had but later abolished the death penalty have fewer killings of police in the line of duty or a lower percentage of murders involving law enforcement victims than states that had and retained the death penalty? And why should police and the public be safer in states that don’t have the death penalty or that have but don’t use it than in states that more aggressively employ it? The answer is that there is no cause-effect relationship between having or not having the death penalty and murder rates.

But it also makes no sense to assert that the statistical correlation between recent death-penalty abolition and greater policer-officer safety is a product of causation. Police officers are not less likely to be killed because a state has not yet abolished the death penalty but will soon do so. Instead, the relationship is the other way around. Murder rates — and particularly the rates at which police are killed — have a political impact, providing highly emotional stories that often define the political narrative and contribute to the political environment in which death penalty abolition does or does not occur.

Those emotional stories often hijack the discussion, diverting legislatures from the true policy issue: does the death penalty work? And when it comes to public safety, the answer is clear. Having the death penalty does not make the public or police safer.

D. The Death Penalty Does Not Deter Mass Shootings.

But even if the death penalty does not deter murders generally or protect police, maybe the threat of death penalty may deter some of the most horrific crimes such as mass killings. With that in mind, the Death Penalty Policy Project analyzed available data on mass shootings to see what the relationship is between where the deadliest U.S. mass shootings have taken place and whether the jurisdictions in which they took place have or don’t have the death penalty.4 Our analysis of the data found the notion that the death penalty is a deterrent to mass shootings is simply false.

To answer the question, DP3 looked to data compiled by the Gun Violence Archive (GVA) from more than 7,500 law enforcement, media, government and commercial sources. We examined every mass shooting in the past fifty years in which ten or more people other than the shooter were killed and compared the death-penalty status of the locations in which the shootings occurred to assess whether, and to what extent, the threat of capital punishment has prevented the most significant carnage from taking place. We found that, since the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the death penalty in 1976, 80% of those mass shootings and 84% of the mass shooting fatalities have occurred in death penalty states or on federal property subject to the federal death penalty.

There have been 30 mass shootings in the past fifty years in which ten or more victims were killed. Twenty-four took place in death penalty states or on federal property. These shootings happened in fourteen different jurisdictions (thirteen states and on federal property in the District of Columbia). Eleven of those jurisdictions (78.6%) authorized the death penalty at the time of the mass shooting.5 Seven states have had multiple incidents in which ten or more victims were killed in mass shootings.6 Six of the seven states (85.7%) had multiple mass shootings with 10+ fatalities despite authorizing the death penalty at the time.7

Collectively, these thirty mass shootings have taken the lives of 540 people and wounded 840 others. 452 of those who were killed (83.7%) and 818 of those who were wounded but survived (97.4%) were shot in death-penalty jurisdictions. Looking at mass shootings in which 20 or more people were killed, 88.9% (eight of nine) took place in death penalty states.

The death penalty has not deterred mass shootings, nor can it. The rational assessment of consequences assumed by deterrence theory simply doesn’t apply to these crimes.

The Violence Project Mass Shooter Database,8 housed at the Violence Prevention Project Resource Center at Hamline University, helps to explain why. The data show that a majority of mass shooters are suicidal, “commonly troubled by personal trauma before their shooting incidents [and] nearly always in a state of crisis at the time.”9 For a potential mass shooter who is suicidal, the threat of judicial execution is not a deterrent. But mass shootings typically never get to that point. According to the National Institute of Justice, “[m]ost [shooters] died on the scene of the public mass shooting, with 38.4% dying by their own hand and 20.3% killed by law enforcement officers.” That’s 58.7% of all mass shootings. DP3’s review of the 30 deadliest mass shootings in the past half-century found that the on-the-scene death toll for the shooters in those cases was even higher. 63.3% (19 of 30) of the individuals who committed these killings did not survive to be arrested, including the shooters in nine of the ten deadliest incidents.

The ubiquity of mental health issues in these cases further underscore why the threat of after-the-fact judicial punishment is not a deterrent. As the Violence Prevention Project Resource Center has noted, 80% of mass shooters “were in a noticeable crisis prior to their crimes,”10 and individuals who are in the throes of emotional crisis do not engage in the rational assessment of consequences required for a deterrent to deter.

The data show that the death penalty is not a tool of public safety when it comes to mass shootings. Its presence has not deterred mass shootings and the data on mass shooters suggests that it cannot do so.

II. Death Penalty Proceedings are Worse for Victims’ Families than Non-Capital Proceedings.

A second question that frequently came up during meetings with legislators was how does the death penalty affect victims’ families? Does it, as is so often asserted, bring families closure? Contrary to the popular narrative, the evidence actually suggests that the death penalty does not facilitate closure11 and is worse for victims’ families, at least when compared to other available punishments.

A study published in the Marquette Law Review12 followed victims’ family members in Texas and Minnesota to compare the impact of the death penalty versus ife without parole on homicide survivors. The study found differences in what it called “survivor well-being,” with family members from Minnesota experiencing “higher levels of physical, psychological, and behavioral health.”13

In both states, the ultimate penal sanction was promoted as doing justice for the victims’ families. However, the study “found that the critical dynamic was the control survivors felt they had over the process of getting to the end.”14 The researchers reported that

In Minnesota, survivors had greater control, likely because the [non-capital] appeals process was successful, predictable, and completed within two years after conviction; whereas, the finality of the [capital] appeals process in Texas was drawn out, elusive, delayed, and unpredictable. It generated layers of injustice, powerlessness, and in some instances, despair. Although the grief and depth of sorrow remained high for Minnesotans, no longer having to deal with the murderer, his outcome, or the criminal justice system allowed survivors’ control and energy to be put into the present to be used for personal healing.15

The New Jersey Study Commission on the Death Penalty referenced similar factors in its 2007 report recommending that the state abolish its death penalty in favor of life without parole. The Commission found that “that the non-finality of death penalty appeals hurts victims, drains resources and creates a false sense of justice.” By comparison, it found that “[r]eplacing the death penalty with life without parole would be a certain punishment, not subject to the lengthy delays of capital cases; it would incapacitate the offenders; and it would provide finality for victims’ families.”16

Other studies have found that the promise that an execution will bring about closure for victims’ family members is illusory. A study led by University of Minnesota sociology-anthropology professor Scott Vollum found that only 2.5% of family members reported achieving “closure” after an execution, while more than eight times that number (20.1%) reported that the execution did not help them heal. Family members in the study also observed that, rather than providing the promised emotional catharsis, the execution “actually increased family members’ feelings of emptiness because it didn’t bring back their loved ones.”17

Moreover, the extended death penalty appeal process and accompanying media coverage repeatedly retraumatizes family members by keeping them “involved in the tragedy for years, even decades, as multiple hearings, appeals and trials drag on.”18 Holding on to the anger for that extended period of time is also damaging to family members’ well-being.

Finally, whether an execution ultimately results in “closure” or not, that promised result is not the final outcome for most death penalty cases. The single most likely outcome in a capital case once a death sentence has been imposed is that the conviction or death sentence will be overturned in the courts and the defendant will be resentenced to life or less.19

III. Use of the Death Penalty as a Bargaining Tool Does Not Increase Pleas or Save Resources, and It Increases the Risk of Wrongful Convictions.

Several legislators raised questions concerning whether the death penalty should be retained so it can be used as a “bargaining tool” or a “stick” to solve crimes, extract guilty pleas, and save resources. However, the evidence again suggests that the threat of the death penalty as a bargaining tool does not increase pleas or save resources, and it increases the risk of wrongful convictions.20

A. The Death Penalty is Not Necessary to Negotiate Guilty Pleas

As an initial matter, more than 90% of convictions in criminal cases are obtained by guilty pleas and there is no evidence that not having a death penalty impairs a state’s ability to resolve cases via pretrial pleas.21 Furthermore, a study of plea practices in New York following reinstatement of capital punishment found that the threat of the death penalty “leads defendants to accept plea bargains with harsher terms, but does not increase defendants’ overall propensity to plead guilty.”22

B. Studies Suggest Resolving a Capital Case by Plea Costs More than Taking a Non-Capital Case to Trial.

Secondly, there is significant evidence from several jurisdictions that those potentially capital prosecutions that are ultimately resolved by plea actually cost more than non-capital prosecutions that proceed to trial.23

Two 2015 fiscal impact studies by the Indiana Legislative Services Agency found that “the out-of-pocket expenditures associated with death-penalty cases were significantly more expensive than cases for which prosecuting attorneys requested either life without parole or a term of years.” The first analysis — prepared on April 13, 2015, as a cost assessment for a bill that would make more cases eligible for the death penalty — found that the average cost of a murder case tried to a jury in which the prosecution sought life without parole was $185,422. The analysis also found that a death-penalty case resolved by guilty plea was $433,702 — more than 2.33 times more costly than a non-capital trial.

A second analysis prepared on May 4, 2015 in connection with a bill to add another aggravating circumstance to the state’s death-penalty statute found that the state’s average expenditure of $285,189 for its share of a death-penalty case resolved by plea was 1.88 times greater than its $151,890 share of a life-without-parole case tried to a jury. It also found that the $148,513 average county expenditure for capital cases that were resolved by plea was 4.43 times greater than the counties’ $33,532 average expenditure for a life-without-parole case tried to a jury.

Likewise, a 2014 Kansas Judicial Council study24 that examined 34 potential death-penalty cases from 2004-2011 found that the trial costs of a capital case resolved by plea were $146,857, including $130,595 in defense costs and $16,262 in district court costs. Collectively, that was 21.9% greater than the $120,517 cost of a non-capital case that went to trial, which included $98,963 in defense costs and $21,554 in district court costs.

Similarly, a September 2010 Report to the Committee on Defender Services Judicial Conference of the United States Update on the Cost and Quality of Defense Representation in Federal Death Penalty Cases25 found that it costs the federal government more to resolve a capital case by plea than to take a non-capital case to trial.

C. Threatening Witnesses and Suspects With the Death Penalty Increases the Risk of Wrongful Convictions.

To the extent that using the death penalty as a “stick” has any positive benefits in solving cases or obtaining guilty pleas, it does so at the grave risk of causing wrongful convictions. The Death Penalty Policy Project is currently reviewing data from the National Registry of Exonerations in an attempt to quantify the severity of that risk. To date, in my prior work at the Death Penalty Information Center and now at DP3, we have reviewed the Registry’s annual exoneration reports from 2016, 2018 through 2021, and 2023.26 In the six years of Registry reports we have examined, we have found 79 cases of exonerations involving the wrongful threat or pursuit of the death penalty, an average of 13.2 exonerations per year.

Contrary to the claim that the death penalty is a necessary negotiating tool or bargaining chip, the data points to a darker truth: threatening people with the death penalty increases the risk of wrongful convictions. And the systemic risk reaches much farther than cases that have put innocent people on death row.

The grave risk inherent in capital punishment — the possible execution of innocent people — is unquestionably serious. The 200 death-row exonerations since Furman v. Georgia was decided in 1972 is a testament to that. But limiting the concept of wrongful use of the death penalty to death-row exonerations grossly understates the frequency with which abusive capital prosecutions and threats to use the death penalty against defendants or witnesses leads to wrongful convictions.

Threatening to kill a person is a crime and a form of psychological torture. When the government does it, it is also a human rights violation. As with other forms of torture, people whose lives are threatened will often provide information to their interrogators. Sometimes that information is truthful, but often it is simply what the witness or suspect believes the interrogator wants to hear.

DP3’s analysis of the 2023 exonerations provides a window through which to assess the extent of the danger posed by death-penalty threats. There were four death-row exonerations in 2023 — a signficant number for a single year. But even that was less than one quarter of the exonerations in 2023 that involved the wrongful pursuit or threat of the death penalty. Prosecutors wrongfully sought the death penalty or obtained wrongful murder convictions in another thirteen cases by using false testimony or confessions coerced by threatening defendants or witnesses with the death penalty. In an additional two cases, prosecutors secured wrongful convictions by threatening a defense witness with the death penalty or pursuing the death penalty against an underaged girl's co-defendant in a separate trial.

Here are some of our findings from the 2023 National Registry data:

The wrongful pursuit or threat of the death penalty contributed to more than 11% of all exonerations recorded by the National Registry in 2023.

Prosecutorial misconduct was rampant in the cases. Official misconduct was present in at least 118 of the 153 exonerations in 2023, or 77.1% of all exonerations during the year. That increased to 85.2% with respect to homicide exonerations (75 of 88 cases). Worse yet, it was present in all 17 wrongful murder convictions obtained with death penalty threats. Sixteen of those cases also involved perjury or false accusation by prosecution witnesses.

The wrongful threat of capital prosecution also had a clearly racially disparate impact. Sixteen of the exonerees (84.2%) were people of color: ten were Black (52.6%) and six Latinx (31.6%). Eleven of the 13 who were wrongfully capitally prosecuted were Black (9) or Latino (2). Three of the four who were wrongfully convicted and sentenced to die were defendants of color, two Black and one Latino.

While the misuse of death-penalty threats was geographically widespread (seven states in the East, Midwest, Southeast, South, Southwest, and Northwest), it was overwhelming concentrated in counties that have long histories of abusive death penalty practices.

Five counties accounted for 15 exonerations linked to wrongful threat or pursuit of the death penalty (including the two cases of indirect death-penalty threats) — Cook County, IL (7 cases), Philadelphia, PA (4), Orleans Parish, LA (2), and Cuyahoga, OH and Oklahoma, OK (one each). Those five counties also account for 40 death-row exonerations (one fifth of the national total) and 78 convictions or death sentences that have been overturned as a result of prosecutorial misconduct or have resulted in exonerations because of prosecutorial misconduct.

The use of the death penalty as a stick may lead to confessions, favorable prosecution testimony, and guilty pleas — but at what cost? It not only raises ethical questions about coercive practices, it also undermines the integrity, reliability, and accuracy of the proceedings in which it plays a part.

IV. Even if the Death Penalty Were Theoretically Justified in Some Extreme Cases, that is not How it is Carried Out in Practice.

We have all heard the claim that the death penalty is reserved for the most extreme cases — the allegedly “worst of the worst.” In practice, however, that claim has become a platitude. Ohio, today, is proof of that.

On April 21, 2016, eight members of a Pike County family — Christopher Rhoden Sr.; Clarence “Frankie” Rhoden; Dana Lynn Rhoden; Gary Rhoden; Hanna May Rhoden; Hannah Gilley; Kenneth Rhoden; and Christopher Rhoden Jr. — were murdered. The so-called “Pike County Massacre” was widely regarded as the worst murder in Ohio history. It led to the most costly crime investigation in the state’s history and special legislation to have state taxpayers pick up a substantial portion of the bill.

Four members of another family — George “Billy” Wagner III; Angela Wagner; George Wagner IV; and Edward “Jake” Wagner — were arrested in November 2018. None will be sentenced to death. Two-and-a-half years later, prosecutors agreed to a plea deal with Jake Wagner that took the death penalty off the table in his case if he agreed to testify against the other members of his family. If he did testify, the deal would also spare his family members.

Now, there may well have been very good case-specific reasons why no one involved in the Pike County Massacre will be sentenced to death. There were very good case-specific reasons why the Green River Killer, Gary Ridgway did not face the death for 49 murders in Oregon and the “Golden State Killer,” Joseph DeAngelo, did not face the death penalty for 13 murders and was not charged with dozens of rapes in California. But whatever those reasons were, they take away any argument that the death penalty in practice is justified because it is narrowly applied only in the worst of the worst cases.

It has long been understood, at least from the time Andrew Welsh-Huggins wrote his classic expose of Ohio’s death penalty in 2009, No Winners Here Tonight: Race, Politics, and Geography in One of the Country's Busiest Death Penalty State, that the state’s capital punishment system was arbitrarily, discriminatorily, and disproportionately applied

Nonetheless, if Ohio is like every other state, the District Attorney’s Association will have appeared before this committee reporting on the graphic details of individual cases and asserting the death penalty is the only acceptable punishment for them. Their testimony, however, will have ignored three important points.

First, there are an equal number of cases just as graphic that did not result in the death penalty. In many of them, prosecutors will have declared that the life sentence ultimately imposed did justice for the victims’ family.

Second, the gruesome nature of the facts clouds our judgment about the fairness of the case. Just because a murder is gruesome doesn’t mean that the person charged with it actually committed the crime. Justice Antonin Scalia famously pointed to the cases of Henry McCollum and Leon Brown, sentenced to death for the brutal rape and murder of a young girl, as the exemplar of the necessity of capital punishment. Although he did not know it at the time, the two intellectually disabled young men were completely innocent. And the facts of the murders in the cases that led to the wrongful convictions of Ohio’s eleven death-row exonerees are also gruesome.

Third, studies show that “the ‘worst of the worst crimes’ produce the ‘worst of the worst evidence.’”27 Examining more than 1,500 cases, University of Denver professors Scott Phillips and Jamie Richardson found that as the seriousness of a crime increases, so did the likelihood that police would produce coerced confessions, some true and some false, and that prosecutors would fill gaps in their cases with more questionable forensic evidence and false testimony from prison informants. The result is a significantly increased risk of wrongful convictions.

V. Conclusion

Once again, I thank you for the opportunity to appear before this committee to assist in your deliberations. I hope my remarks have helped address some of your questions on this important issue.

— Robert Dunham

See Robert Dunham, DP3 Study: After 1,600 Executions, the Public and Police are Safer in States with No Death Penalty, Death Penalty Policy Project (Nov. 18, 2024), https://dppolicy.substack.com/p/dp3-study-after-1600-executions-the.

Life After the Death Penalty: Implications for Retentionist States, Committees on Capital Punishment of the New York City Bar and the American Bar Association’s Section of Civil Rights and Social Justice (August 14, 2017), https://web.archive.org/web/20180325194333/https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/files/pdf/Life-After-Death-Penalty_Transcript.pdf.

See note 1, supra.

See Robert Dunham, DP3 Analysis: The Death Penalty Does Not Deter Mass Shootings, Death Penalty Policy Project Substack (July 22, 2024), https://dppolicy.substack.com/p/dp3-analysis-the-death-penalty-does.

Alabama, California, Colorado, Florida, Nevada, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia, Washington state, and the federal government. Colorado had two mass shootings with ten or more fatalities while it had the death penalty and has had a third such shooting after abolition. Three other non-death-penalty states — Connecticut, Maine, and New York — have had mass shootings with ten or more fatalities.

Texas has had six such incidents; California, four; Colorado, Florida, and New York, three each; and Pennsylvania and Virginia, two each.

New York was the only non-death-penalty state with multiple mass shootings in which ten or more victims were killed.

National Institute of Justice, Public Mass Shootings: Database Amasses Details of a Half Century of U.S. Mass Shootings with Firearms, Generating Psychosocial Histories (Feb. 3, 2022), https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/public-mass-shootings-database-amasses-details-half-century-us-mass-shootings.

Violence Prevention Resource Center, Key Findings (archived webpage), https://web.archive.org/web/20240802001113/https://www.theviolenceproject.org/key-findings/.

See Death Penalty Information Center, Science Challenges Myth that Death Penalty Brings Victims’ Families Closure (May 13, 2019), https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/science-challenges-myth-that-death-penalty-brings-victims-families-closure; Linda Lewis Griffith, Does the death penalty give victims closure? Science says no, San Luis Obispo Tribune (May 6, 2019), https://www.sanluisobispo.com/living/family/linda-lewis-griffith/article230010544.html; Caitlin McNair and Robert T. Muller, Death Penalty May Not Bring Peace to Victims' Families, Psychology Today (Oct. 19, 2016), https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/talking-about-trauma/201610/death-penalty-may-not-bring-peace-victims-families.

Marilyn Peterson Armour and Mark S. Umbreit, Assessing the Impact of the Ultimate Penal Sanction on Homicide Survivors: A Two State Comparison, 96 Marq. L. Rev. 1 (2012), https://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol96/iss1/3/.

Id. at 97.

Id. at 98.

Id.

N.J. Death Penalty Comm’n, Death Penalty Study Commission Report 61 (2007), https://pub.njleg.gov/publications/reports/dpsc_final.pdf.

Griffith, supra note 11 (describing the results of the Vollum study).

Id.

Death Penalty Information Center, Death Penalty Census, https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/facts-and-research/death-penalty-census.

One of the legal reforms to prosecutorial practices proposed as part of 21 Principles for the 21st Century Prosecutor is: “Don’t threaten to seek the death penalty to coerce a plea.” Brennan Center for Justice, Fair and Just Prosecution, The Justice Collaborative, 21 Principles for the 21st Century Prosecutor at 23 (2018).

Ilyana Kuziemko, Does the Threat of the Death Penalty Affect Plea Bargaining in Murder Cases? Evidence from New York’s 1995 Reinstatement of Capital Punishment, 8 American Law and Economics Review 116, 118 (2006), https://kuziemko.scholar.princeton.edu/sites/g/files/toruqf3996/files/kuziemko/files/death_penalty_0.pdf.

Id.

See generally Death Penalty Information Center, State Studies on Monetary Costs, https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/policy-issues/costs/summary-of-states-death-penalty.

Report of the Judicial Council Death Penalty Advisory Committee (Feb. 13, 2014), https://dpic-cdn.org/production/legacy/KSCost2014.pdf.

Jon B. Gould and Lisa Greenman, Report to the Committee on Defender Services Judicial Conference of the United States Update on the Cost and Quality of Defense Representation in Federal Death Penalty Cases (Sept. 2010), https://www.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/fdpc2010.pdf.

See Robert Dunham, DP3 Analysis: More Than 10% of U.S. Exonerations in 2023 Involved Wrongful Use or Threat of the Death Penalty, Death Penalty Policy Project Substack (Apr. 17, 2024), https://dppolicy.substack.com/p/dp3-analysis-more-than-10-of-us-exonerations; Robert Dunham, DPIC Analysis: At Least a Dozen Exonerations in 2021 Involved the Wrongful Threat or Pursuit of the Death Penalty, Death Penalty Information Center (Aug. 26, 2022), https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/dpic-analysis-at-least-a-dozen-exonerations-in-2021-involved-the-wrongful-threat-or-pursuit-of-the-death-penalty; Robert Dunham, DPIC Analysis: 13 Exonerated in 2020 From Convictions Obtained by Wrongful Threat or Pursuit of the Death Penalty, Death Penalty Information Center (Aug. 6, 2021), https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/dpic-analysis-13-exonerated-in-2020-from-convictions-obtained-by-wrongful-threat-or-pursuit-of-the-death-penalty; Robert Dunham, DPIC Analysis: Use or Threat of Death Penalty Implicated in 19 Exoneration Cases in 2019, Death Penalty Information Center (Oct. 23, 2020), https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/facts-and-research/dpic-reports/dpic-special-reports/dpic-analysis-2019-exoneration-report-implicates-use-or-threat-of-death-penalty-in-19-wrongful-convictions; Robert Dunham, Wrongful Use or Threat of Capital Prosecutions Implicated in Five Exonerations in 2018, Death Penalty Information Center (Apr. 23, 2019), https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/wrongful-use-or-threat-of-capital-prosecutions-implicated-in-five-exonerations-in-2018; Robert Dunham, DPIC Analysis: Causes of Wrongful Convictions, Death Penalty Information Center (May 31, 2017) (at least 13 exonerations in 2016 that involved either a wrongful capital prosecution or a prosecution in which false testimony was presented after police or prosecutors threatened a defendant or a witness with the death penalty), https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/stories/dpic-analysis-causes-of-wrongful-convictions.

Scott Phillips and Jamie Richardson, The Worst of the Worst: Heinous Crimes and Erroneous Evidence, 45 Hofstra Law Review 417 (Apr. 2017), https://dpic-cdn.org/production/legacy/PhillipsRichardsonArticle.pdf.

The Death Penalty Policy Project (“DP3”) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization housed within the Phillips Black Inc. public interest legal practice. DP3 provides information, analysis, and critical commentary on capital punishment and the role the death penalty plays in mass incarceration in the United States.