Executions are Up but the Sky is Not Falling

The Execution Frenzy by Death Penalty Zealots has not Translated to Increased Public Support for the Punishment

Executions in the United States are up — way up — in 2025. But despite rising anxiety among death penalty abolitionists, the sky is not falling. Because “up” is a relative term, and even with the wave of new death warrants this year and the resumption of executions in a few mostly deep red states, executions are still down — way down — from their peak at the turn of the century.

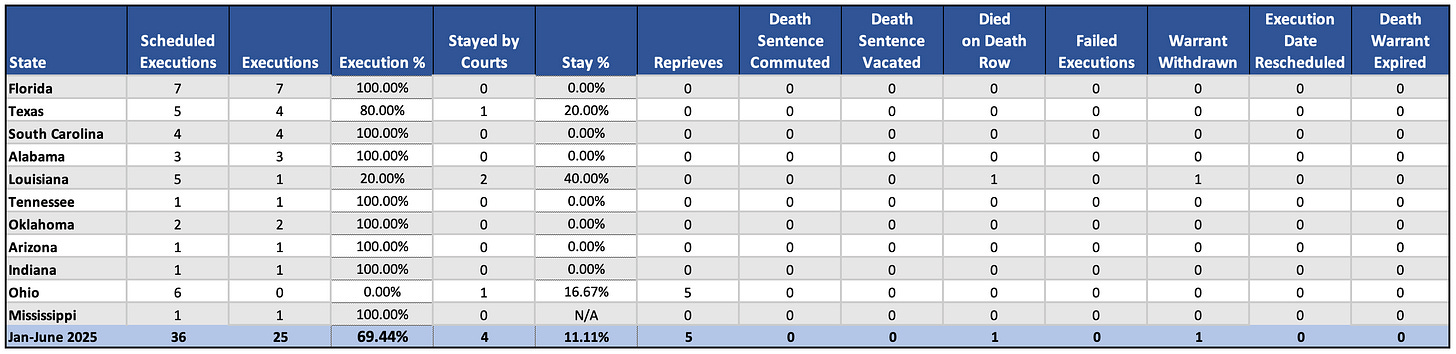

Except in Florida, where in the second half of his final term as governor Ron DeSantis is attempting to position himself among the far right wing of his party as a potential successor to Donald Trump, the U.S. is nowhere near a record breaking number of executions. Florida has executed nine men — one third of the nation’s 2025 total — through August 1, with two more executions already scheduled. But there were 98 executions in 1999 and we are unlikely to reach half that number in 2025. Public opinion polls show opposition to capital punishment at a fifty-year high and new death sentences in 2025 are near historic lows.

So what accounts for the increase in executions, and what is skewing the numbers?

It is a Trump effect — but not in the manner that the media is reporting. There is no upswing in public confidence that our state and federal governments can fairly and reliably impose and carry out death sentences. I believe the stacking of a now extremist Supreme Court, which has emboldened and empowered states to flout the constitution on a broad range of issues, is the main driver of the rise in executions.

The death penalty is a canary in the coal mine of the assault on decency and democracy currently underway in the United States. The norm-shattering federal execution spree in the final months of the first Trump term was a harbinger of the Court’s now habitual abandonment of its constitutionally assigned institutional role as a protector of the rule of law. During that first-term execution spree, the justices lifted every stay of execution and vacated every injunction issued by federal judges — whether Republican or Democratic, ideologically conservative, centrist, or liberal — who had determined that death sentenced prisoners were likely to prevail on the merits of the challenges they had raised to their executions or, at a minimum, that the issues they had raised were sufficiently meritorious to deserve further evidentiary and legal development.

But the right-wing majority of the Court knew that if they followed the traditional rules of appellate judging and deferred to the preliminary-stage findings of the lower federal courts, Donald Trump would be out of office by the time those courts issued their rulings in the cases and irrespective of whether those rulings were pro-defendant or pro-death, the executions likely wouldn’t happen. So damn the constitutional torpedoes, full speed ahead with the executions.

Nor was the 2020-2021 federal execution spree the sole signal of the Court’s result-orientation in death warrant litigation. Since the Trump appointees tilted the Court’s ideological center, it has granted only one stay of execution to consider the constitutionality of a death sentence or capital conviction. And in that case,1 a state attorney general found the evidence of prosecutorial misconduct so extreme and so convincing that he joined the defendant in advocating for a stay and calling for a new trial.2 Even then, the Court scheduled the case for conference a dozen times before adding its own question to the issues presented for review to see if there was a procedural technicality the Court could interpose to avoid granting relief.3 And then it appointed special friend-of-the-court counsel to argue against the defendant and the attorney general.4

The states that want to carry out executions have gotten the message: except in the most extraordinary of extraordinary circumstances, they are free to carry out executions come what may.

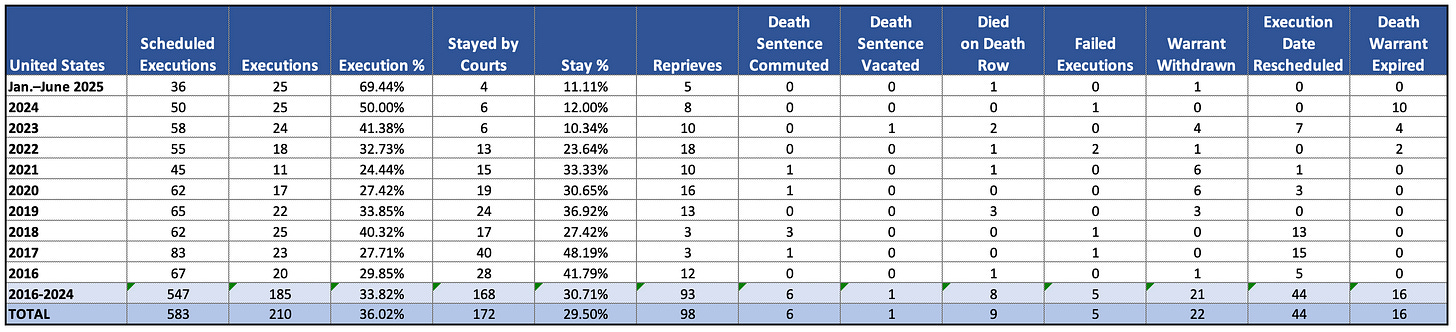

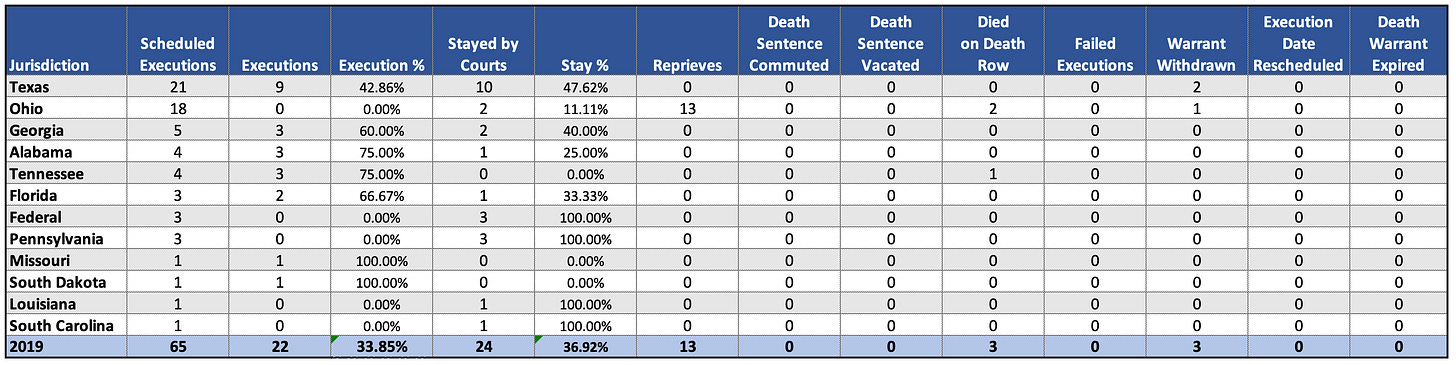

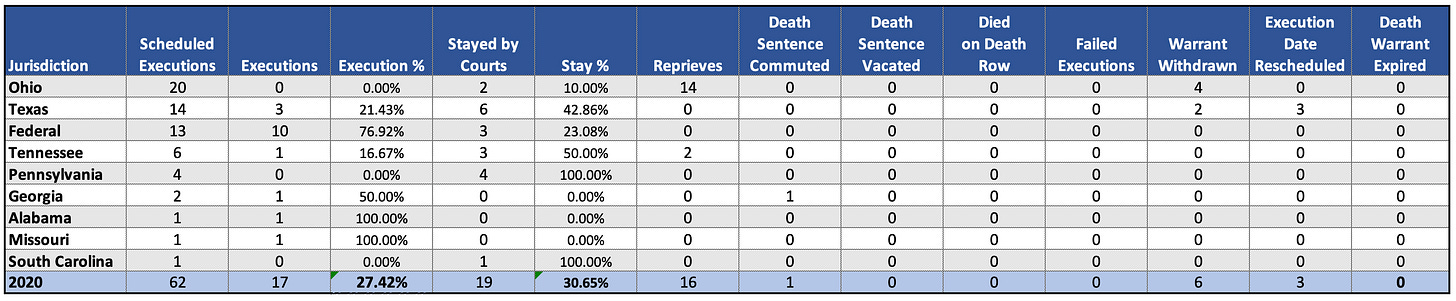

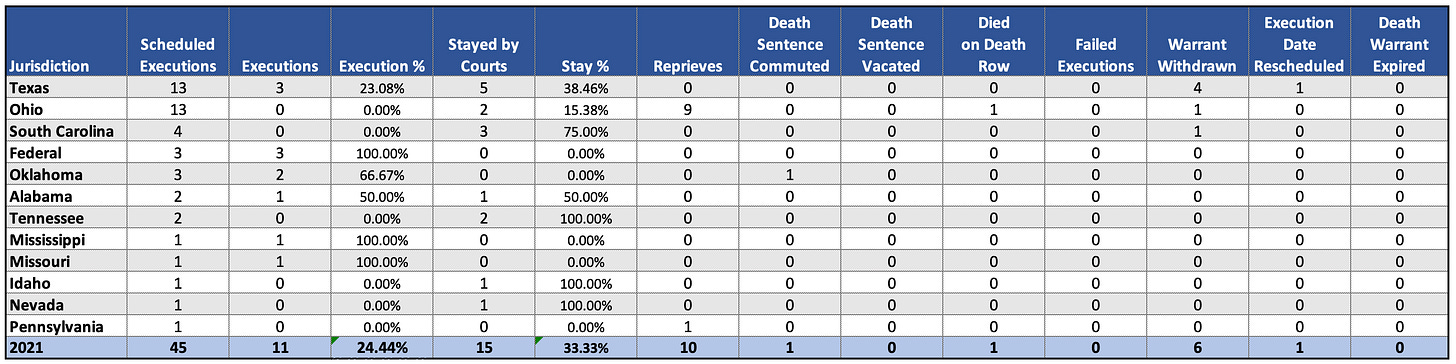

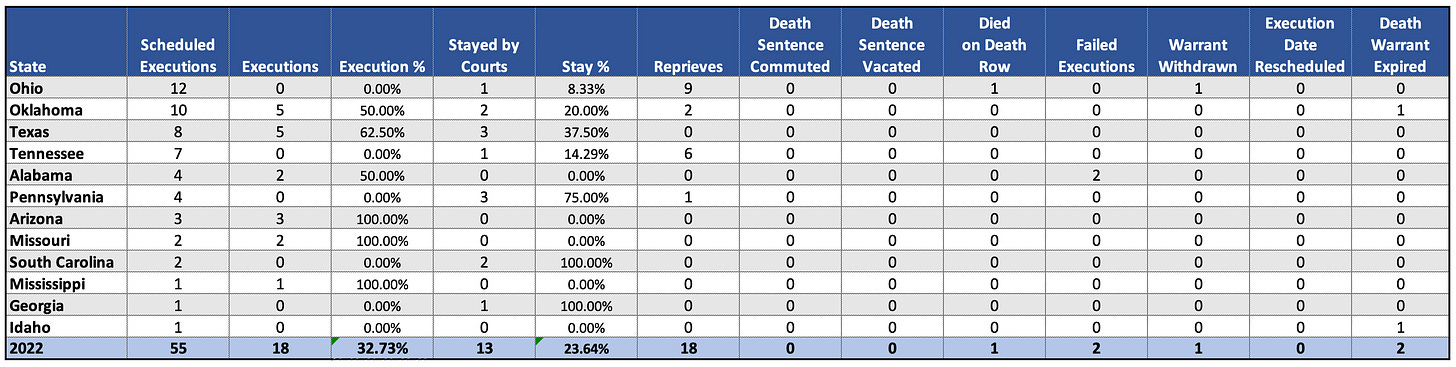

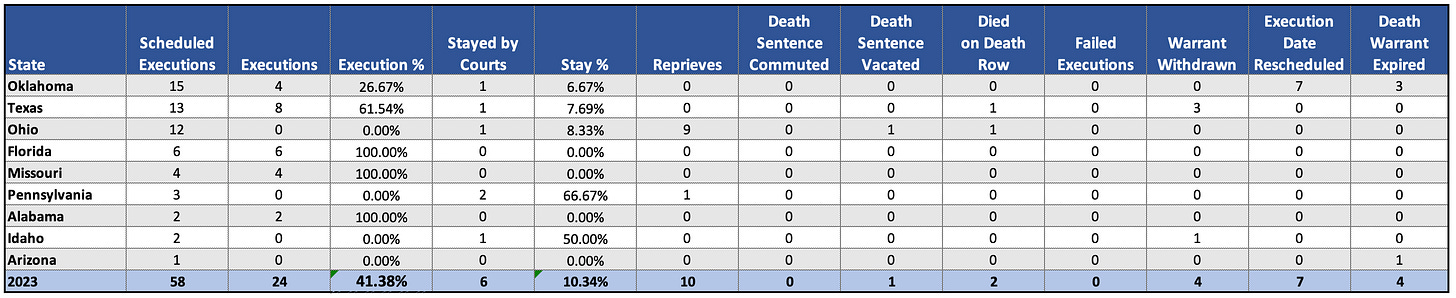

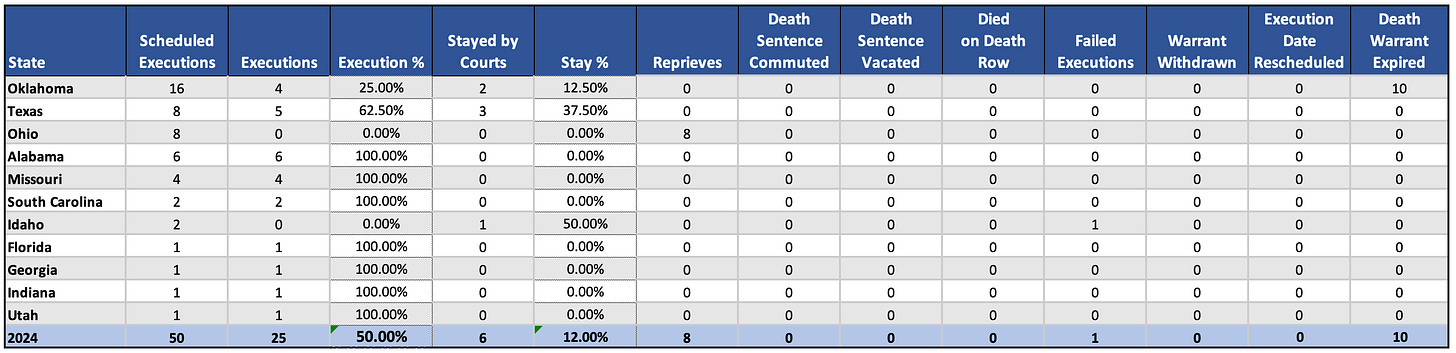

The loss of the federal courts as a backstop against unconstitutional executions is both driving up the number of executions and emboldening states to engage in unlawful conduct as they attempt to do so. The impact is clear. (See the tables below.) This year, death warrants are resulting in executions at about twice the rate of the previous nine years (69.4% vs. 33.8%). Courts are granting stays of execution about 3 times less frequently (11.1% vs. 30.7%).5 Here are two examples:

Texas

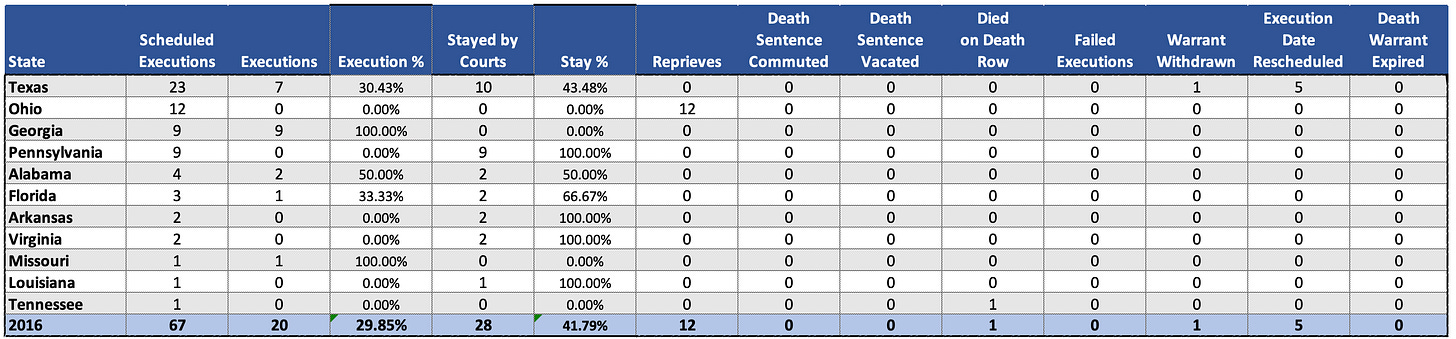

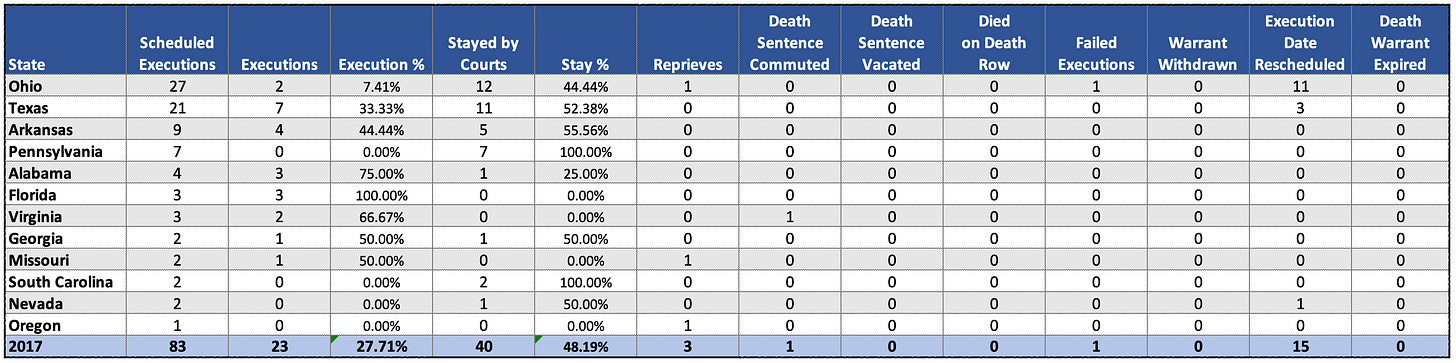

In 2016 and 2017, Texas carried out 14 executions. In that same two-year period, state and federal courts granted 21 stays of execution in Texas cases.

Since January 2023, Texas has carried out 17 executions. In that same two-and-a-half-year period, state and federal courts have granted 5 stays of execution.

The likelihood that a Texas death warrant will result in an execution rather than a stay is 5.1 times greater today than in the rest of the past decade.

Florida

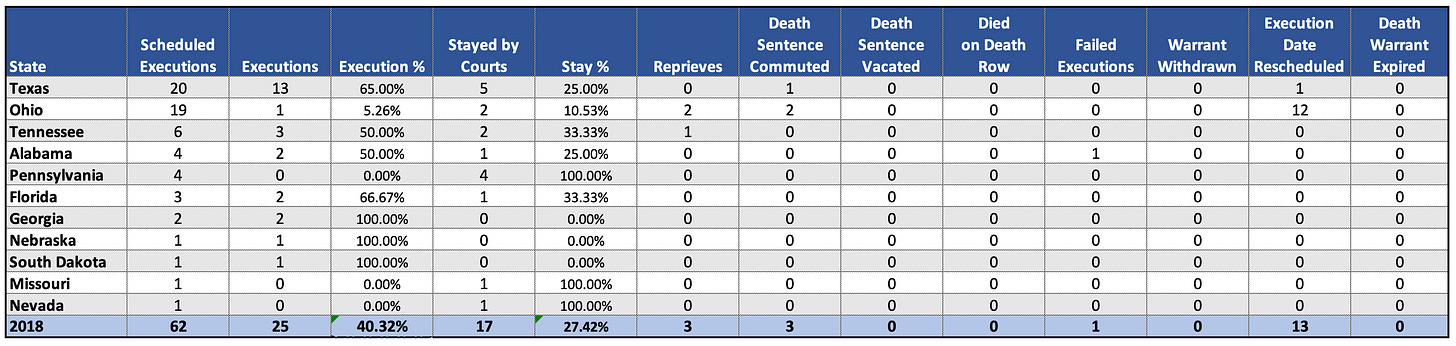

From 2016 through 2019, Florida scheduled 12 executions. Eight were carried out and courts stayed 4.

Since January 2023, Florida has scheduled 16 executions. Courts didn't stop any of them.

When I became executive director of the Pennsylvania Capital Case Resource Center in 1994, I began tracking the issuance and outcomes of death warrants in the state. I broadened that inquiry nationally shortly after I became executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center in March 2015 and I have continued to track warrant outcomes after I left DPIC and started DP3 in 2023. I've put together a spreadsheet that allowed me to create the tables below, which break down the outcomes of the death warrants issued since January 2016.

There is no perfect predictor of death warrant outcomes nationally. Every state has its own story. Ohio has lots of reprieves and rescheduled executions. Pennsylvania is statutorily required to issue death warrants that it won't carry out. Oklahoma jumped headlong into a 25-executions-in-29-months spree, then backed out of it because of the stress on corrections personnel. But even with some idiosyncratic statistical noise in the background, the execution vs. stay trend is striking.6

Outcomes of U.S. Death Warrants, 2016–June 30, 2025

That is not to say that the Supreme Court is solely responsible for the rise in executions. A second major factor is that states that want to carry out executions now appear to have the ability to do so, either by surreptitiously (and most likely illegally) obtaining drugs for executions or by putting in place alternative methods of executions (Alabama and Louisiana — gas suffocation; Tennessee — electric chair; South Carolina — firing squad). Of course, the U.S. Supreme Court has been complicit in this by permitting states to use secrecy statutes to conceal illegal practices in procurement and defects in their execution processes and placing on condemned prisoners the burden of producing in litigation the information states have unconstitutionally withheld from them. That is an evidentiary Catch-22 that would not be tolerated in any other litigation setting.

The execution surge has not been truly national in scope. … 26 of the 27 executions so far in 2025 (96.3%) have been in former enslavement jurisdictions. States have carried out 131 executions since January 2019. 128 of them (97.7%) have been in former Confederate states, states or territories that were claimed by the Confederacy, or in other territories that permitted slavery.

Yet even with this judicial encouragement, the execution surge has not been truly national in scope. A combined 33 of the 76 executions since January 2023 (43.4%) have been in Texas (17) or Florida (16). Overall, the execution surge has been confined almost exclusively to jurisdictions that, as states or territories at the time of the civil war, practiced slavery. By my count, 26 of the 27 executions so far in 2025 (96.3%) have been in these former enslavement jurisdictions.7 States have carried out 131 executions since January 2019. 128 of them (97.7%) have been in former Confederate states, states or territories that were claimed by the Confederacy, or in other territories that permitted slavery.8

Not surprisingly, these executioners have exhibited a striking white-victim bias in their recent executions. As I wrote in my Substack article, Surge in U.S. Executions Exhibits Huge White-Victim Preference:

"Forty-four of the 50 executions carried out between January 1, 2024 and June 30, 2025 (88.0%) involved at least one white victim and 43 (86.0%) involved only white victims. Thirty of the final 31 executions during that execution surge in the U.S. (96.8%) came in cases with only white victims. The last 22 of those executions involved only white victims, one short of the longest spree of executions involving just one race of victims in the modern history of the U.S. death penalty."

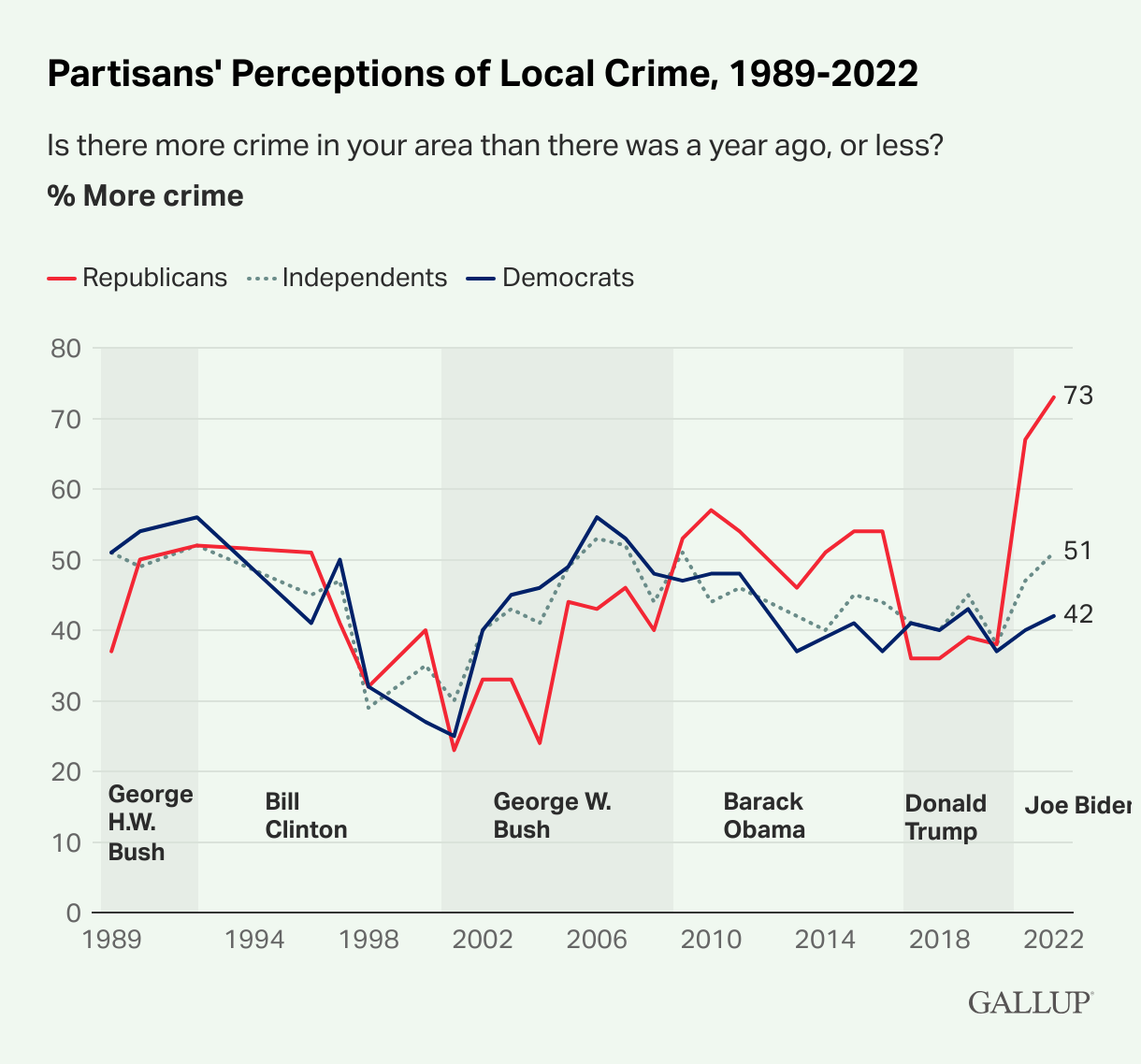

But the executioners are out of touch with the public. The fear-mongering on crime that was epidemic in the 2022 mid-term and 2024 presidential election cycles has had no appreciable impact on public opinion about capital punishment.9 Every indication so far is that public support for capital punishment remains at or about a 50-year low. While the belief among Republicans that crime is up reached record highs, support for capital punishment was down.

In Gallup’s annual crime survey in 2022, conducted during the midst of the mid-term elections, Gallup found that a record number of respondents said they believed local crime was up. But there was an overwhelmingly partisan dimension to the numbers. Nearly double the percentage of Republican respondents said local crime was up, compared to the numbers just two years before. A record 95% of Republicans expressed the view that crime was up nationally. But during that same period, there were only modest or minimal increases among the numbers of Independents and Democrats who perceived that crime had risen.10

As I wrote in an analysis for DPIC in December 2022, “[a]t the same time that the belief that crime was rising increased, Gallup found that support for capital punishment remained just one percentage point above the [then] 50-year low of 54% recorded in 2021. And in the same two-year period in which Gallup found that Republicans’ perception that local crime was rising skyrocketed by 35 percentage points, Republican support for capital punishment fell from 82% to 77%.”11

The results from the two polls suggest that the crime ads had their greatest effect on individuals who were already the most racially fearful and predisposed to support the harshest criminal sanctions — i.e., those who already supported the death penalty. However, the often overtly racist crime ads did not drive up support for the death penalty among African Americans — the community most directly affected by crime and, at 81%, the group of voters most likely to tell Gallup that crime was an important issue to them during the midterm elections. Yet concern about crime levels did not translate into support for the death penalty — a policy that is widely perceived to symbolize the U.S. mass incarceration practices that have disproportionately victimized the African American community.

In the past two years, support for capital punishment nationwide has fallen another percentage point to a new 50-year low of 53%.12 At the same time, a record number of Americans now believe the death penalty is unfairly applied.13 And in the Fall of 2023, with near record-low death sentences and near general lows in executions, 56% of Gallup respondents said that the death penalty was being imposed “too often” or “about the right amount.”14

The polling data also presage a continued erosion of public support for capital punishment going forward. Gallup reports double-digit generational gaps in support for the death penalty across all political affiliations. Support for capital punishment is 13 percentage points lower for Generation Z and Millennial Republicans and Independents than it is for their Generation X and older compatriots. Even among Democrats, who collectively averaged 38% support for the death penalty from 2020–2024, support is 11 percentage points lower among Millennials and those in Generation Z.15

The October 2025 Gallup survey will tell us more, but the brazen misconduct of the executing states and the refusal of the courts to intervene to halt executions that are at best questionable is more likely to raise the public’s level of disenchantment with capital punishment than it is to boost public support for the penalty.

Finally, new death sentences are a better indicator of public sentiment about the death penalty than executions are. New death sentences are down from 2024 and are on pace to match the numbers imposed in the lowest non-pandemic years since the resumption of capital punishment in the U.S. in 1972. The Death Penalty Information Center has reported that only ten new death sentences were imposed in the first half of 2025.16 And while this-year-to-last-year comparisons don’t tell us very much about either the past or the future, the long term trend remains clear. People continue to come off death row at a faster pace than new sentences are added.

The bottom line? The U.S. death penalty is not sustaining itself. The extremist practices that have led to the current execution surge neither represent nor reflect any trend towards increased public confidence in or desire for the death penalty.

For death penalty abolitionists, the short-term forecast is stormy. But the sky is not falling.

Glossip v. Oklahoma, No. 22-7466.

Brief for Respondent, State of Oklahoma, in Support of Petition for Writ of Certiorari, Glossip v. Oklahoma, No. 22-7466 (July 5, 2023).

Order List at 2 (Jan. 22, 2024) (“In addition to the questions presented, the parties are directed to brief and argue the following question: Whether the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals’ holding that the Oklahoma Post-Conviction Procedure Act precluded post-conviction relief is an adequate and independent state-law ground for the judgment.”).

Corrected Order List at 1 (Jan. 26, 2024) (“Christopher G. Michel, Esquire, of Washington, D. C., is invited to brief and argue this case, as amicus curiae, in support of the judgment below.”).

The calculations are through June 30, 2025. There were two more executions in July and none of three scheduled July executions was stayed. Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine granted a reprieve of the third scheduled execution and rescheduled that execution for July 2028.

Data from 2016 through 2022 from the Death Penalty Information Center. See Death Penalty Information Center, Outcomes of Death Warrants in 2016; Death Penalty Information Center, Outcomes of Death Warrants in 2017; Death Penalty Information Center, Outcomes of Death Warrants in 2018; Death Penalty Information Center, Outcomes of Death Warrants in 2019; Death Penalty Information Center, Outcomes of Death Warrants in 2020; Death Penalty Information Center, Outcomes of Death Warrants in 2021; Death Penalty Information Center, Outcomes of Death Warrants in 2022. The data from 2023 on is from the Death Penalty Policy Project’s independent tracking of death warrant outcomes.

2025 executions through August 1: Former Confederate states (23 executions) — Florida (9); Texas (4); South Carolina (4); Alabama (3); Louisiana (1); Tennessee (1); Mississippi (1). States that as territories practiced slavery (3 executions) — Oklahoma (2); Arizona (1). Union states (1 execution) — Indiana (1).

2024 executions — 24 of 25 in states that were members of or were claimed by the Confederacy or in territories that permitted slavery. Former Confederate states (15 executions): Alabama (6); Texas (5); South Carolina (2); Florida (1); Georgia (1). States claimed by the Confederacy (4 executions): Missouri (4). States that as territories practiced slavery (5 executions) — Oklahoma (4); Utah (1). Union states (1 execution) — Indiana (1).

2023 executions — 24 of 24 in states that were members of or were claimed by the Confederacy or in territories that permitted slavery. Former Confederate states (16 executions): Texas (8); Florida (6); Alabama (2). States claimed by the Confederacy (4 executions): Missouri (4). States that as territories practiced slavery (4 executions) — Oklahoma (4). Union states (no executions).

2022 executions — 18 of 18 in states that were members of or were claimed by the Confederacy or in territories that permitted slavery. Former Confederate states (8 executions): Texas (5); Alabama (2); Mississippi (1). States claimed by the Confederacy (5 executions): Arizona (3); Missouri (2). States that as territories practiced slavery (5 executions) — Oklahoma (5). Union states (no executions).

2021 executions — 8 of 8 in states that were members of or were claimed by the Confederacy or in territories that permitted slavery. Former Confederate states (5 executions): Texas (3); Alabama (1); Mississippi (1). States claimed by the Confederacy (1 execution): Missouri (1). States that as territories practiced slavery (2 executions) — Oklahoma (2). Union states (no executions). In addition, there were three federal executions for defendants sentenced to death in Virginia, Missouri, and Maryland.

2020 executions — 7 of 7 in states that were members of or were claimed by the Confederacy or in territories that permitted slavery. Former Confederate states (6 executions): Texas (3); Alabama (1); Georgia (1); Tennessee (1). States claimed by the Confederacy (1 execution): Missouri (1). Union states (no executions). In addition, there were ten federal executions for defendants sentenced to death in Texas (4), Missouri (2), Arizona (1), Arkansas (1), Georgia (1), and Iowa (1).

2019 executions — 21 of 22 in states that were members of or were claimed by the Confederacy or in territories that permitted slavery. Former Confederate states (20 executions): Texas (9); Alabama (3); Georgia (3); Tennessee (3); Florida (2). States claimed by the Confederacy (1 execution): Missouri (1). States in territories that did not permit slavery (1 execution) — South Dakota (1).

Robert Dunham, Midterm Elections: Moratorium Supporters, Reform Prosecutors Post Gains Despite Massive Campaign Efforts to Tie Reformers to Surge in Violent Crime, Death Penalty Information Center, Dec. 6, 2022; Polls: Death Penalty Support Remains Near 50-Year Low Despite Record-High Perception that Crime Has Increased, Death Penalty Information Center, Nov. 15, 2022; Megan Brennan, New 47% Low Say Death Penalty Is Fairly Applied in U.S., Gallup.com, Nov. 6, 2023; Jeffrey M. Jones, Drop in Death Penalty Support Led by Younger Generations, Gallup.com, Nov. 14, 2024.

Megan Brennan, Record-High 56% in U.S. Perceive Local Crime Has Increased, Gallup.com, Oct. 28, 2022.

Robert Dunham, Midterm Elections: Moratorium Supporters, Reform Prosecutors Post Gains Despite Massive Campaign Efforts to Tie Reformers to Surge in Violent Crime, Death Penalty Information Center, Dec. 6, 2022.

Megan Brennan, New 47% Low Say Death Penalty Is Fairly Applied in U.S., Gallup.com, Nov. 6, 2023; Jeffrey M. Jones, Drop in Death Penalty Support Led by Younger Generations, Gallup.com, Nov. 14, 2024 (according to Gallup’s October 2024 annual crime survey, “overall support for the death penalty in the U.S. has fallen to 53% today, a level not seen since the early 1970s”).

Megan Brennan, New 47% Low Say Death Penalty Is Fairly Applied in U.S., Gallup.com, Nov. 6, 2023.

Id.

Jeffrey M. Jones, Drop in Death Penalty Support Led by Younger Generations, Gallup.com, Nov. 14, 2024.

Anne Holsinger, Mid-Year Review 2025: New Death Sentences Remain Low Amidst Increase in Executions, Death Penalty Information Center, July 7, 2025.